A Photo Lesson from the Painting Wyeths

Avoiding the merely scenic to find 'essence'

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

I remember telling Jamie Wyeth where he should have breakfast in Americus, Georgia as he traveled with us on a crowded press bus after Jimmy Carter won his post-Watergate election to the White House in 1976.

Perhaps it was because we were the same age, among veteran White House and political reporters mostly decades older, that Wyeth and I shared a relaxed conversation on the bus during that cold dark evening in the South. He did not go into detail, but the artist—who even then was world famous—said he was there to do a portrait of the president-elect. Seemed to make sense to me--and something told me not to pry.

What I did do was ask what it was like to draw Carter, whose face during the 1976 presidential campaign was most often depicted in caricature or political cartoons as all teeth and squinty eyes. The most arresting thing about Carter, Wyeth told me, was his sun-damaged skin: the result of Carter, an Annapolis grad and nuclear engineer, earning his early living under a hot sun as a peanut farmer in Plains, Ga. before going fulltime into Democratic politics.

“But when he smiles it all really comes together,” Wyeth went on, echoing the near-universal reaction to Carter’s broad Pepsodent grin.

I suspect, too, that’s why Jamie Wyeth’s ultimate portrait of Carter did not include a smile—the much too obvious path for so talented an artist as he. The final version, now in the National Portrait Gallery, shows a very serious Carter staring intently into the distance, bright blue eyes alert, even wary, with not a tooth in sight. (And my subsequent years of covering Carter for the New York Daily News showed him to be an extremely intelligent man—who did not suffer fools.)

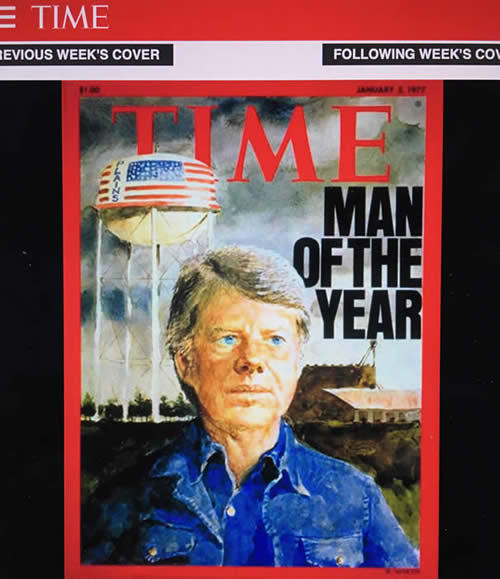

My suspicions about the Wyeth portrait were correct: it soon appeared on the cover of Time Magazine’s Jan. 3, 1977 issue celebrating the new president as ‘Man of the Year.’

|

Jamie Wyeth's depiction of a non-smiling Jimmy Carter made Time's Man of the Year cover. |

About to turn 77, Jamie Wyeth, as everyone knows, is the son of the late Andrew Wyeth, who often is called the greatest American painter of the 20th century—and grandson of N.C. Wyeth, a renowned painter and book illustrator, whose striking color images of pirates, heroes and castaways graced collector’s editions of Treasure Island, Robin Hood, Kidnapped and Robinson Crusoe.

All three of these towering artists shared one artistic trait: they avoided depicting the obvious or the common, even when painting familiar settings and subjects.

All three also loved rural Maine—from where, in fact, I am writing this column—and each took pains to avoid visual cliché.

“Port Clyde is meaning a great deal to me,” N.C. Wyeth wrote to a colleague in 1923, referring to the rocky mid-coastal town where he had bought a tumbledown house as a summer retreat for him and his large family, including young Andrew. Still, N.C. longed to “outgrow the picturesqueness of [the] appeal of the country and its inhabitants,” hoping to avoid the merely scenic to capture more of the region’s “essence.”

Skip a generation and here is Jamie Wyeth—the Wyeth most associated with Maine because he now lives there fulltime—and you get a similar response:

“The problem with Maine is it’s so emblematic—the lobster traps, the sunsets,” he told writer Lori Douglas Clark in Bangor Metro Magazine in 2006. “There’s that bucolic image [of Maine islands], but winters are tough. Islanders are singular people and I identity with that sense of isolation.” Still, he said, “you can be alone and not be lonely.”

Like his famous forebears, Jamie Wyeth was, and is, wary of the tantalizing allure of the outwardly beautiful and superficially scenic.

And so we should be as photographers.

In Paris, for exmple, do you really need to make the millionth-plus photograph of the Eiffel Tower, especially a full length view? Here's what I did more than 40 years ago:

|

| 'Eiffel Tower Abstract,' from my book, Recovered Memory: New York & Paris 1960-1980. © Frank Van Riper All rights reserved. |

I am not saying glorious landscapes are not, well, glorious, especially on a perfect day of blue skies and marshmallow clouds. Just that these photographs are not likely the ones that will set you apart as a photographer.

Here in Lubec, Maine, where Judy and I have had a summer place for nearly 40 years, everyone and their cat has made a photo of the candy-striped lighthouse at West Quoddy Head state park—literally the easternmost point in the US. Years ago, leading a dawn photo workshop there, I chose instead to concentrate on the morning light as it raked across gorgeous ancient striated rock:

|

Raked by dawn's light, these rocks at Quoddy Head appealed to me more than the candy-striped lighthouse. © Frank Van Riper |

The rock pic illustrates an old photography teaching tool: when you see something that first catches your eye (e.g.: the lighthouse), look behind you and see if there’s also something else worthy of a shot--or three.)

Most recently, I have been doing a series of close-up, mostly BxW, portraits of flowers and plants simply to illustrate why for years I hated having to judge pedestrian floral close-ups at camera clubs. Almost always shot in color, seemingly at high noon, some poor flower posed smack in the middle of the frame. The flower had done all the work; the photographer had done nothing more than push his or her shutter release.

I submit that such ten-a-penny pictures can’t match a dramatically studio-lit portrait (as portrait it is) done with an eye, not just to one flower, but to overall composition:

|

| 'Calla Lilies,' made in the studio with directed flash to emphasize their shape and leaves. © Frank Van Riper |

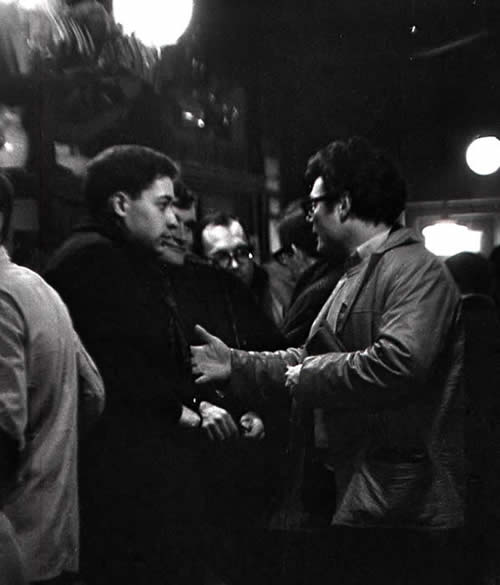

The People Conundrum: Too many photographers can’t overcome their fear of photographing people, when the truth is most folks don’t give a damn about you, especially if they are absorbed in what they are doing—as were these guys 50 years ago at McSorley’s Old Ale House in Manhattan…

|

| 'McSorley's Ale House,' from Recovered Memory: New York & Paris 1960-1980. © Frank Van Riper |

Segue ahead 30 years—back to Lubec, Maine—and I am photographing a tent revival meeting for my book Down East Maine / A World Apart. This pic (below) didn’t just happen.

Before the service, I asked permission to address the congregation, saying I was a documentary photographer working on a book about life in Maine. If any folks did not want to be photographed, I said, just raise your hand. Once they knew who I was and what I was doing, they relaxed—and I became invisible. (n.b.: similar “access” can be had on the fly simply by smiling at your subject and pointing to your camera. Works 9 times out of 10.)

|

| 'Tent Revival, Lubec, Maine,' from Down East Maine / A World Apart. © Frank Van Riper |

Finally, My wife Judith Goodman and I have completed work on our next book, The Green Heart of Italy: Umbria and its Ancient Neighbors. Our first book in color, you can bet there will be plenty of lovely scenics, like this one that I shot…

|

| © Frank Van Riper |

But, for us—documentary photographers to whom people are the soul of our work--it’s photos like these two of Judy’s below that will separate our book from a cavalcade of others featuring only postcard shots of hillsides and ruins:

|

|

© Judith Goodman (2) |

In the first shot, Judy—who speaks virtually no Italian—simply smiled at this simpatico group of old guys enjoying the company of the little dog. After a few minutes she just raised her camera and made the money shot. In the second photo, at the Dionigi vineyards, these two needed no prompting as they harvested Sagrantino grapes for some of the finest wine in Italy.

-0-0-0-0-0-

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, Lubec, Maine

Join us for another magical summer in Down East Maine in 2023...

Master Photo Classes with Frank Van Riper

I have taught in several different places—from Washington DC to Umbria—but my Photo Master Classes in Lubec, Maine may be my favorites for their small size (five students max) and their remarkable setting—arguably the most beautiful coastline in the United States. (Sorry, route 1 in California.)

These intense, three and a half-day, limited enrollment classes are aimed at the more advanced student, who already has taken a photo workshop and who is familiar with basic flash. Maximum enrollment of just five. Open to vaccinated students ONLY. Enrollment through the famed SummerKeys Music and Arts workshops in Lubec, Maine--the easternmost point in the United States. First class will be July 17th-19th, 2023; second will be August 7th-9th. NB: previous Master Classes were booked almost immediately.

More Information: GVR@GVRphoto.com

To enroll: www.SummerKeys.com

Come photograph in one of the most beautiful spots on earth.

-----------

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 6/20/23]

|