Go Back to current Column

NEW: Frank Van Riper classes for Fall/Winter...see below

Edward Hopper and the ‘Decisive Moment’

An American realist painter captures life in a photographic style

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

My long fascination with the work of the American realist painter Edward Hopper (1882-1967) probably began decades ago; the first time I saw his iconic depiction of a sun-streaked street in the city of my birth, entitled “Early Sunday Morning” (1930).

Hopper, himself a New Yorker for most of his adult life, often referred to the painting as “Seventh Avenue Shops” and the image achieves a kind of broad-shouldered eloquence with its nearly-abstract horizontal ribbons of red and green—the green of storefronts topped by the dull red of the brick superstructure—interspersed every so often with bright yellow window shades. Hopper painted the scene raked by strong morning sunlight, and the long shadows of the dawning day add to the impact of this austere, even minimalist, image. (So minimalist in fact that the names of the businesses on the glass fronts of the shops are merely suggested by bands of blurry grey--in what otherwise seems to be a highly detailed painting.)

|

Edward Hopper’s classic painting “Early Sunday Morning” (1930) is a minimalist symphony, caught at the moment—early morning—when sunlight plays dramatically against lower Manhattan storefronts. (Whitney Museum of American Art)

|

So too did Hopper’s most famous painting “Nighthawks” (1942) rivet my attention in ways I did not immediately understand.

There was something about the mood and lighting of this piece—so often copied or parodied as it worked its way into the public mind—that appealed to me, not just as a viewer of a painting, but as a photographer.

As a photographer, I appreciated the way the lighting inside the all-night eatery contrasted with the nighttime gloom of its surroundings. As a photographer, too, I sensed there was something about the relationship of the four forlorn figures in the diner that created a unified whole—the way the lone figure to the left leads us to the seated man and woman facing us, and how the counterman to the right, seemingly caught just as he is about to speak to them, also directs our gaze at this desolate, or perhaps just bone-weary, couple.

“Nighthawks” (1942) typifies Hopper’s talent for creating The Decisive Moment on canvas—note how the two figures on either side of the couple draw our eye to them. (The Art Institute of Chicago)

It took several other Hopper paintings—as well as those of other painters whose work seemed flat, uninteresting or plainly artificial—before I realized what had so held my interest.

Edward Hopper had captured on canvas, with paint and brush, the Decisive Moment—the holy grail of documentary photographers who long to capture not only objective reality before their lens, but a telling moment or gesture that speaks to a more universal condition among us all.

That is one compelling reason to see the huge Hopper retrospective at the National Gallery of Art’s East Wing in Washington (running through January 21).

To be sure, Hopper was justly lauded for his landscape work—he can be viewed in context with such giants as Winslow Homer and Thomas Hart Benton. His early years produced many canvases of buildings and other outdoor scenes in New England: Gloucester, Massachusetts, various places in Maine and, finally, in Truro on Cape Cod, where he and his wife built a home and studio to go along with the well-loved space in Greenwich Village where he lived until his death in 1967.

But I have to say that these images do not appeal to me nearly as much as Hopper’s enigmatic canvases containing people. A heroic “portrait” of a New England lighthouse, raked by late afternoon light, is fine as far as it goes—goodness knows I see many such scenes every year when we summer in Lubec, the easternmost town in Maine’s easternmost county. But that is all it is. Despite Hopper’s own admission that his prime ambition as an artist was “to paint sunlight on the side of a house,” I keep coming back to everything this prolific artist has done containing people.

|

| In “Lighthouse Hill” (1927) we see an example of Hopper’s deft hand at landscape. But my heart belongs to his peopled paintings. (Dallas Museum of Art) |

Let’s be clear, though: Edward Hopper was not a great portraitist—although a wonderfully rendered self-portrait is one of the best things in this excellent exhibition. In fact, scholars whom I presume to be far more informed than I on the subject routinely criticize Hopper’s figure work, especially of woman, and more especially his nudes. [Virtually all of his women, by the way, are based on studies of his wife, the painter Josephine Nivison.]

On this point I must disagree. I find his figure work excellent—especially his nudes. As we art critics say: go figure.

But if Hopper’s style, especially viewed through the prism of today, evokes criticism in some quarters for, among other things, his widely known rejection of the “pure painting” of abstraction, no one with walking around sense can criticize the man for his ability to make pictures that stir emotions and raise questions.

“Images that evoke rather than narrate,” curator Carol Troyen deftly puts it.

And therein lies Hopper’s appeal, I think, to a whole generation of people—Americans especially, since he was painting in their bailiwick, not in Europe—who have grown used to seeing photography as one of the most accurate ways, if not the most accurate way, of reflecting life and its fleeting, often ambiguous, moments.

Hopper does this far too often for it to be accident.

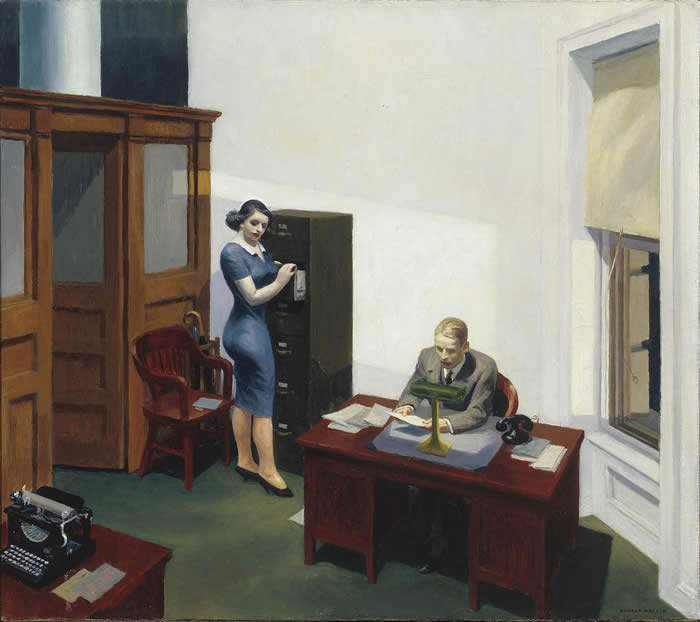

If “Nighthawks,” for example, depicts an almost desolate exhaustion in the people shown, there is an almost sexual electricity in “Office at Night,” (1940) in which a voluptuous secretary in a tight blue dress stands at a filing cabinet looking distracted, and clearly not paying attention to her filing, staring at (one assumes) her boss, seated at his desk just a few feet away in the confined space. He seems to be concentrating on the document he is holding. Or is he just marking time? It is after hours—obvious from the play of light and shadow—and one assumes these two are alone in the office, perhaps even in the building. Why? What is happening? Or, more important, what is about to happen? Even the perspective of the painting--from above the two subjects--suggests a voyeuristic fly-on-the-wall, which, in itself, heightens the incipient sexual tension.

|

I think it is impossible to ignore the sexual tension in “Office at Night” (1940), though one could easily imagine the next moment being mundane and innocent. The fly-on-the-wall perspective is found in other Hopper works as well. (Walker Arts Center)

|

It is a wonderfully caught moment—and wonderfully ambiguous. In the very next moment, will the secretary simply resume her search through the files and will the man dial the phone to his left and tell his wife that he will be home shortly? Or will the two fall into each other’s arms, confident that no one can see them?

Hopper’s unusual perspective, looking from above, through building windows, in this and other New York paintings, may seem odd to some--but not, I imagine, to other New Yorkers. It is this very voyeuristic perspective one has every time one rides the elevated subway—in my case the Jerome Avenue IRT in the Bronx—and Hopper seems to have used his subway excursions as sources of inspiration. Little slices of life passing before him with each clatter of the subway’s wheels

One of my favorite Hopper paintings also captures what many have called Hopper’s “cinematic” style.” And in fact, the painting is named “New York Movie.” Made in 1939, it captures two separate events of far different intensity happening simultaneously, as if on the screen. (Interestingly, several major movie directors, including Alfred Hitchcock, Ridley Scott and Wim Wenders, have cited Hopper as an influence.)

The painting is set in one of Broadway’s once-grand movie houses, the Palace on Times Square. The horizontal image is literally cut in two—a split-screen, if you will. On the left, in the shadows, the sparse audience watches the black and white film unfold before it (note Hopper’s inspired used of shape and shadow to evoke movement on the screen.) But on the right, seemingly lit by a spotlight, is a beautiful blonde “usherette,” her legs encased in billowy slacks, leaning against the wall in the corridor.

|

Hopper influenced a number of famous film directors, including Hitchcock and Wim Wenders, with his “cinematic” style. In “New York Movie” (1939) he in effect “split-screens” two events: audience watching film, and usherette lost in her own thoughts under gorgeous light. (The Museum of Modern Art)

|

Her attitude is puzzling. Is she lost in thought—her arms crossed in front of her, right hand to her chin? Or is she wracked by worry or concern over something far beyond the theater? [If this painting ever were to achieve the renown of “Nighthawks” and therefore be subject to parody, today’s version would simply have talking on her cell phone.]

Or is the girl simply tired, waiting for the movie to end so that she can go home?

It is this wonderful ambiguity—created by Hopper when he decided to depict this girl at this moment—that creates visual tension and interest.

We see this young woman in this position in this image and immediately we are interested in her.

That is the mark of a good painting.

Or of a good photograph.

Frank Van Riper is Washington-based commercial and documentary photographer, journalist and author. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. Among others, he is the author of the biography Glenn: The Astronaut Who Would Be President, as well as the photography books Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart. His book Talking Photography is a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over the past decade. Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved.]

Study with Frank Van Riper at Glen Echo PhotoWorks, 2007-08

Flash Photography Demystified ($95)

Stop being intimidated by your flash. Frank's intense, user-friendly one-morning hands-on seminar will help you beat your flash unit into compliant submission. (Sunday, February 3, 2008, 10am-1pm)

Documentary Photography: Digital or Film ($300)

Taught by an acclaimed documentary photographer and author. Will help students document their world, more easily photograph people, and work in unfamiliar surroundings. Film or digital welcome. (6 weeks, Thursdays, November 1-December 13 (no class Nov. 22) 7-10:30pm) ALSO: Thursdays, February 7-March 13, 2008, same time

Field Trip: National Gallery of Art, East Wing ($150)

3-meeting National Gallery of art, East Wing, workshop. A brief organization meeting a week before the trip, with the follow-up critique a potluck dinner at Frank's home. Beginning when the doors open at the NGA you will find endless opportunities for shooting--people, architecture, abstracts--all in beautiful light. (Field Trip, Sunday, November 4. Contact instructor for additional dates: gvr@gvrphoto.com or 202.362.8103.

Online registration:

www.glenechopark.org (“Classes & Workshops,” then “Fall, Winter 2008”)

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. published 10/15/07]

|