Go Back to current Column

'Lobbyists': For Better or Worse, Just Like Us

Neil Selkirk's new book shatters the Abramoff cliche

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

Some months ago, as photographer Neil Selkirk sought to drum up publicity for his latest book Lobbyists (Nazraeli, $60), he got this snarky reply from a Washington-based financial reporter, responding to the publisher’s press call to a private viewing and book-signing:

“Will the lobbyists be caged or hung on the walls?”

Neil responded in kind:

“You get the top score for witty cocktail party repartee. I’ve been dining out on it for the last week…Now, do you have the nerve to show up on Tuesday and see if your assessment is worthy, or are you the cynic of your words, who would rather indulge [him]self in private or with others too jaded to actually look…”

The newsie was a no-show. Whether because of his own cynicism or because he had been bested with a riposte worthy of Oscar Wilde, it didn’t matter. It was his loss.

Selkirk’s book—more a large hardcover monograph of 60 portraits with corresponding biographies at the back—is an illuminating counter to the clichéd view that Washington lobbyists are corrupt, over-fed, over-moneyed guns-for-hire who live to peddle influence and to buy and sell the only other life form lower than they: politicians.

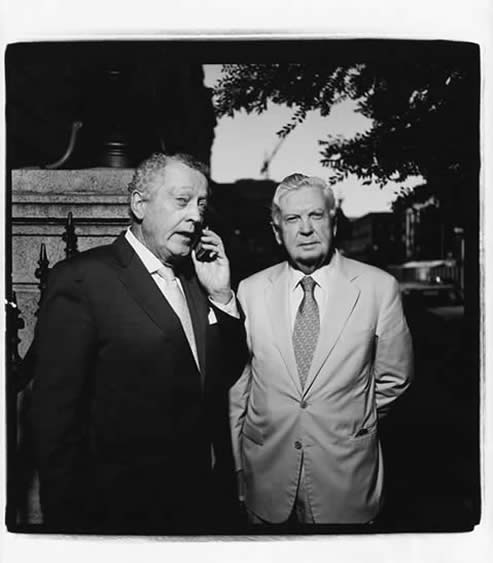

The brothers Thomas (l.) and Paul Quinn, lobbyists in different DC law firms, grace the cover of Selkirk’s book and capture what may be the typical image of the high-powered lobbyist—down to the ever-ringing cell phone. Their government and legal credentials go back decades. (all photographs © Neil Selkirk.)

In the end, it turns out, lobbyists are just like the rest of us, only more so. The shysters and the SOB’s among them may seem larger than life, given their money and influence, but the rest—the majority—are like us too: only more driven, more dedicated (sometimes even by idealism), more knowledgeable (about their clients and causes), more willing to stand up and be counted for what they believe, and to do so for weeks, months—even years--on end with never any guarantee of success.

[This, I might add as a onetime, and longtime, political writer, is a pretty good description of the average member of congress, public pre-conceptions to the contrary notwithstanding.]

There is this eternal: one person’s sniveling lobbyists is another’s shining advocate. And what Selkirk has done in his eloquent book is put a human face on that conundrum.

And, I am happy to say, Neil did it all in black and white—on film—and printed every one of his images himself in the darkroom. This book not only is an important document of our political time, but a glorious paean to the unrivaled power of the black and white silver image.

Selkirk’s photo odyssey began two years ago with an assignment from Aperture magazine to document—in a small portfolio—the lobbying life amid the turmoil of the ongoing Jack Abramoff scandal. Abramoff, you will remember, was the mega-lobbyist who finally pleaded guilty last year to three felony counts involving bribery and corruption charges amid multiple thousands of dollars in gifts and favors to members of congress. One such member, former Rep. Robert W. Ney (R-Ohio), was forced to resign his seat amid a federal corruption probe, and his guilty plea to a multi-part criminal “information” brought on largely by Abramoff’s testimony in a jail-avoiding plea deal with the government.

“I'm sure Abramoff was part of what caused Aperture to do the story,” Neil told me recently in a long e-mail conversation, “but once I started meeting these people I was just blown away by what an intense and exquisite microcosm of the whole human drama they represented. This applies to the idealists, the hired advocates, and those operating in a moral and ethical world that I simply can't comprehend--and sometimes all these are the same person.”

“I started with a small handful of very powerful people that came from (Washington art dealer and gallery owner) George Hemphill. Once I had Tommy Boggs, Mike House and Tom Quinn, only a few turned me down.”

Selkirk’s portrait of lobbyist Tovah LaDier (perhaps before a meeting with clients in what could be any number of DC conference rooms?) She is managing director of the International Biometric Industries Association, a group concerned with the use of biometric information in ID cards, driver’s licenses, airport security.

I remember well when Neil started this gig. Knowing of my own background as a Washington political reporter, he asked me to suggest names of people he might photograph. This led me to poll my own colleagues—including a former student who works in a high-powered DC public relations firm—and there started the inevitable geometric progression that happens when one does the critical initial reporting on a story.

“I had an alternative entrée that began with my daughter's boyfriend's brother, and an old chum who lives in Paris,” Neil said. “They led me to the hard core political idealists--Jamie Love, Asia Russell, Judy Guerin [representing, respectively, the Consumer Project on Technology, global AIDS projects, and efforts to promote “sexuality as a positive, personal, social and moral value.”]

“By and large, if they didn't want their picture taken, I didn't chase them. Once I had them, they were invariably willing to recommend others, sometimes in most unexpected directions. To my great surprise, I had no confrontations of any kind with people in uniform [police, guards, etc.]--I was occasionally asked what I was doing, and was always allowed to proceed.”

“The biggest surprise was that the most professional and pro-active

organization I dealt with was the NRA [National Rifle Association]. Both [CEO] Wayne LaPierre and [legislative action director] Chris Cox and their staffs were helpful, involved and supportive.”

Wayne LaPierre (top), Vice President and CEO of the National Rifle Association is one of the best known (and sometimes most-reviled by liberals) lobbyists in Washington. Less well known, but a frequent witness on Capitol Hill, is Judy Guerin, vice president of the Woodhull Freedom Foundation, advocating sexual freedom for all groups.

In all, there is a stunning ordinariness to Neil’s Lobbyist portraits. Which is not to say they are mediocre—in fact, just the opposite. These portraits are achingly real: you sense that the people depicted here are just the way they are, and are not striking a pose for the photographer, which adds immensely to their value as visual documents. In fact, Neil is known for never overtly prompting his subjects—and, in his documentary work, anyway, for never “dressing the set” to make his subjects more “interesting.” [Suffice it to say that Neil would never tell a lobbyist for the dairy industry to pose in a bathtub full of milk—as Annie Leibovitz had Whoopi Goldberg do years ago for a wonderful portrait for Rolling Stone.]

In most every case, Selkirk’s subjects stare directly into his Hasselblad, looking bemused, intense, relaxed, wary—but always engaged and caught at the right moment. In almost every case, too, you can see how his subject’s environment helps the portrait. How, for example, Tommy Boggs, the quintessential insider, looms with a knowing grin in his doorway—a corridor to influence--as if to say “come in and let’s deal.”

Thomas Hale Boggs, Jr, chairman of the mega-lobbying/law firm of Patton Boggs. Tommy helped craft the Chrysler bailout on ’79 and currently numbers more than 50 corporations, trade associations and state and foreign governments among his clients. The son of the late congressman Hale Boggs, he is the brother of NPR’s congressional correspondent Cokie Roberts.

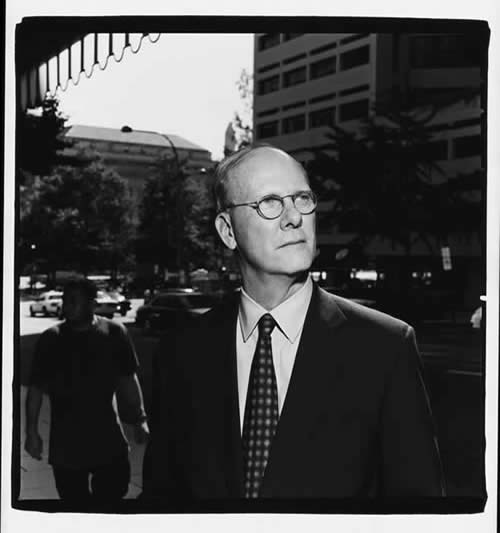

Or see the interesting contrast of forms in the close-up, flash-lit street portrait of Hogan and Hartson’s top lobbyist Mike House. A balding man with wire glasses and a far-away stare, House looks into the middle distance in his suit and tie, dominating the frame, while a barrel-chested man in a dark T-shirt approaches from the left, his muscular form making an ironic counterpoint to the slightly built—yet in many ways much more powerful—House.

W. Michael House, top lobbyist for DC’s largest law firm, Hogan & Hartson. (’Nuff said.) His wife, Gina Joy Rigby House, also is in Selkirk’s book: she’s the lobbyist for AFLAC.

Then there’s Shelley Fidler, an absolute contrast to the buttoned down Mike House. She stands on a street corner in the waning light of afternoon, hands on her hips, handbag on her shoulder, ample chest straining against her simple longsleeved pullover. Her gaze is intense; you want to hear what she’s saying. And, given her background in environmental issues at the state, congressional and White House level, what she is saying is probably worth hearing.

Shelley Fidler, an energy, environment, and natural resources lawyer/lobbyist, with a long history at all levels of government. Arguably, one of Selkirk’s most accessible portraits, and one that questions the stock image of the slick, sleazy lobbyist.

If Selkirk’s work reminds you of Diane Arbus, it should not surprise. As a talented young photographer, just arrived in New York from his native England, he studied under Arbus in the 70s, became her friend, and after her untimely suicide, was trusted by the family to be the sole photographic printer for the Arbus estate—a role he pursues to this day. Like Arbus, Selkirk is a master black and white printer and his work in this book betrays the same attention to photographic detail that Arbus showed in her work.

So it was an interesting exercise to try to guess the equipment Neil used to produce it all: cameras, lenses, film and photographic paper.

I did pretty well, but there were some surprises.

Knowing Neil for so long, and having studied location lighting under him, I knew his penchant for less being more, and for his love of one light source held directly overhead. So I guessed an old Norman 200B strobe unit.

Close, Neil said.

“I gave the 200B to a student a year or two ago--the unit never failed me, but the batteries very often did. I switched to a Lumedyne for Lobbyists, but the 200B reflectors fit the Lumedyne, so the light itself is identical.” [Personal note: this was almost exactly the setup that my wife Judy and I used for years for our location work. Now we are using Quantum Q-flashes, again with near-identical results.]

“You were right on the 80 and the 150.” Neil added, referring to the workhorse 80 mm (normal) and 150mm (tele) lenses for the Hasselblad. “But you didn't pick up the jaw-dropping Hasselblad 350mm Tele Superachromat f/5.6 T* CFE ($6,767.95) which nailed Angela Hofmann [lobbyist for Wal-Mart] from a considerable distance and Keith Ashdown [Taxpayers for Common Sense.] I've owned and used all the Hasselblad long lenses and have honestly, literally, ranked them with lenses that cost less than $100 new--they were unusably bad, but with the new 350, I forgive them their crimes of the last 50 years.”

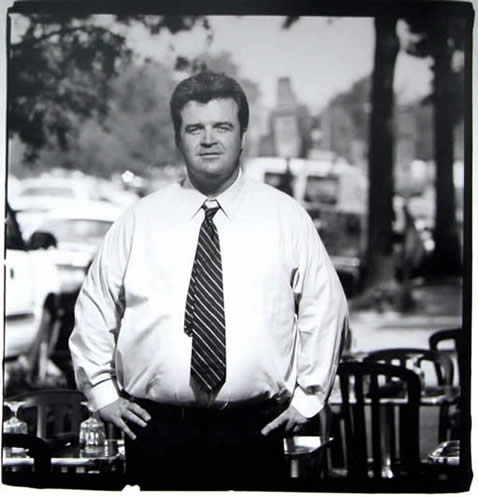

Selkirk’s portrait of Keith Ashdown, VP at Taxpayers for Common Sense, used a huge Hassy telephoto to compress the background and throw it out of focus. The result is an almost three-dimensional image of the budget watchdog who coined the term “Bridge to Nowhere.”

As for the prints: “the prints were made entirely by me (what fun I had) on Forte Glossy VC Warmtone, developed in Beers [developer].”

But what film? I had guessed Tri-X and was feeling pretty confident.

“Try another 50 or 60 guesses at the film and I'll give you the answer…,” my friend and colleague taunted me.

I could have had 100 guesses and I still would not have gotten it.

“Efke 50. A remake of Adox KB17 which left us in the mid-60's and [was] a favorite of Ms. Arbus. Now manufactured by our friends in Croatia, and often difficult to locate. I actually used Adox in my ‘yute’, and a print from a 35mm negative caused a minor sensation at a college interview. I think I bought it more out of nostalgia than anything else but the prints are good and came very easily.” [The film, for those interested, was developed in Beutler developer.]

Thus did Neil Selkirk document a broad cross-section of the men and women who advocate causes and who lobby congress, it must be remembered, and our behalf.

“Mostly I was blown away by scale of the inside-/outside- the-Beltway disconnect. I would not have believed it possible for the two worlds to be so utterly oblivious of each other if I had not seen it to be so again and again.”

Asia Russell is a medical anthropologist and urban ethnographer who directs an international group promoting universal access to affordable HIV treatment, especially in the southern hemisphere.

In his brief introduction to this wonderful book of portraits, Neil writes: “The image of the lobbyist, received through the usual channels by those of us who live outside the confines of Washington, DC, is so monotonously despicable that surely—given the richness of human nature—the reality behind that image must be more complex and intriguing…”

And so it is; and so did Neil Selkirk reflect that in his photographs.

When I pressed him on this—on how he related to this microcosm—Neil said simply:

“You got it Frank--I liked them all.”

Frank Van Riper is Washington-based commercial and documentary photographer, journalist and author. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. Among others, he is the author of the biography Glenn: The Astronaut Who Would Be President, as well as the photography books Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/A World Apart. His book Talking Photography is a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over the past decade. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved.]

|