Go Back to current column

Inside the 'Dark Chamber'

A high- and low-tech way to play with the camera obscura

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

A convincing case can be made that old world painters mastered the depiction of perspective once they discovered how to use the “camera obscura.”

This “dark chamber” or, more prosaically, “dark room”—not to be confused with the modern-day darkroom in which photographic prints are made—allowed artists of centuries past to project an image of the outside world on to a wall, then copy the outlines of that real world image on to their canvases or parchments in absolutely correct perspective.

No more truncated hillsides, no more differing vanishing points. Here, finally, was a tool that allowed such masters as Vermeer and Hals, Canaletto and Holbein, to capture the world in all its elusive, fleeting richness and variety. And still later, the same principal, used with the more intricate (and portable) “camera lucida,” enabled painters like Jean-Dominique Ingres to capture in real time the beautiful (and maddening to reproduce) folds of voluptuous fabric—and so much more.

Who actually discovered the principal of the camera obscura is unknown (reference to it can be found during the time of Aristotle and during the 5th century, BC) but its operation is simplicity itself, based on what later was discovered to be the immutable behavior of light in space.

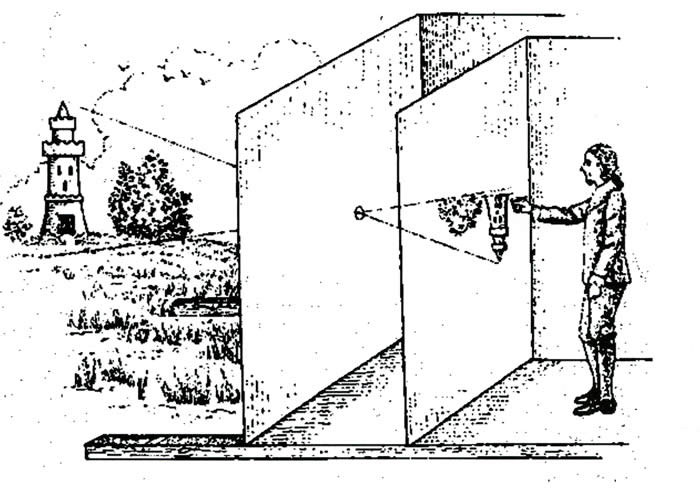

Light travels in a straight line. When it is forced through a small hole, or aperture, into a place in which no other light appears (i.e.: a “dark room”) it can reveal the outside objects it is illuminating as a bright, strikingly detailed image (albeit upside down and reversed) on a blank surface at the far end of the darkened room. Note: it is the small hole that is crucial here—this minimizes distortion and makes a visible projected image possible; otherwise light on the far wall would be just that: light with no image.

|

| An early drawing showing the principle of the camera obscura. Note that projected image through empty hole is upside down and reversed. |

“One pinhole of light can carry all of the visual information of a landscape into a darkened room,” notes writer and critic Luc Sante commenting on the camera obscura photography of the Cuban-born photographer Abelardo Morell. In the past, painters like the Italian master Canaletto or the Dutch genius Vermeer are believed to have used portable, tripod-mounted, dark chambers to view scenes, then record those scenes on grid-scored paper or parchment. Once a small, perfect-perspective, image was drawn it could be reproduced on canvas--correctly oriented and made larger through use of the grid--to become the basis, or “cartoon,” for the final painting.

Even today, Sante writes, this seems like a miracle.

Last summer Leslie Bowman, a photographer friend and colleague, recreated this miracle multiple times during a long afternoon of camera obscura photography in which my wife Judy and I were an eager participants. Leslie is a well-known photographer, painter and photo editor who divides her time between Trescott, Maine, and Bangor—where she is photography editor of Bangor Metro Magazine. Leslie was perfecting her camera obscura technique before a grant-funded fall workshop that she was planning. She invited us along for the practice run-through—as well as to make a photo or two.

|

Not exactly Halloween, just my own, way-long exposure of photographer Leslie Bowman making photo of camera obscura image. That bright light behind her actually is daylight coming through a hole barely a 1/4-inch wide. (Frank Van Riper) |

Our “dark chamber” was just that--and huge. It was a cavernous, high-ceilinged room at the Tides Institute and Museum in Eastport, Maine, a grand old converted bank building that sits at one end of Eastport, the easternmost city in the US.

[For readers of this column who know of my affinity for Down East Maine, Eastport is the country’s easternmost city, but nearby Lubec, where Judy and I live during the summer, holds the clear title as the nation’s easternmost point, with the beautiful West Quoddy Head Lighthouse jutting confidently into the Atlantic, way beyond Eastport, at Quoddy Head State Park. Why is this easternmost point called West Quoddy Light? E-mail me for the answer:GVR@GVRphoto.com ]

The Tides Institute site was perfect because the building was freestanding, meaning it offered window views from several sides, thereby making possible a number of different camera obscura images of Eastport. But before the first exposure could be made, all of the two-storey high windows in the room had to be masked in black plastic to create our “dark chamber.”

Once this was accomplished (twice, it turned out, since one layer of plastic was not enough to keep out all the light) Leslie was ready to plot her shots, and make her tiny holes in the plastic. To insure the holes would be uniformly round—mimicking a lens opening, Leslie taped metal washers over the jagged holes to insure their uniformity. She had researched camera obscura technique from a number of sources: the internet as well as the gorgeous book by Abelardo Morell, titled simply Camera Obscura (Bulfinch, $60).

|

|

Top: Leslie's set of washers that would provide a uniformly round hole through which light would pass during her long exposures. Bottom: Leslie (r.) and daughter Zel prepare to create a glass-less "lens" for their next photo. (Yes, that white dot in the plastic will be the only light source for the picture.) (Frank Van Riper) |

Morell’s wonderful images included shots made in New York in which an upside down and surprisingly detailed Manhattan panorama appears on the blank wall of a darkened room in a high-rise building--a chair or two anchoring the bottom of the image to give the viewer an unsettling perspective. To capture these images in the most detail, Morell set up a film-loaded, tripod-mounted, view camera and, working in the pinhole-lit dark, made very long time exposures of the projected images. For her work, Leslie hoped she would not have to make exposures as long as Morell’s since she would be working digitally.

No sweat, I told her on the phone before the shoot. I noted that, on a whim just a few days earlier in Lubec, I had made a handheld and surprisingly stable digital image of the Big Dipper glowing in a brilliant night sky—and the exposure had only been 15 seconds. Note: the exposure was “handheld” only in the sense that I was not on a tripod. In fact, I was sitting on a lawn chair and balanced my Nikon D300 on my chest as I made the exposure and held my breath. The slight vibration in the image likely was caused by the beating of my heart—and there was nothing I could do about that.

|

| "Handheld" photo of Big Dipper in brilliant night sky in Maine. I was in a lawn chair and rested my D300 on my chest for 15 seconds. Not bad after a few beers. (Frank Van Riper) |

For the trial photos in Eastport, Leslie and I were not aiming for gallery-quality images. We simply wanted to perfect the technique and see how different conditions affected the final outcome. But even with our cameras cranked up to maximum ISO (and even with the attendant increase in digital noise) the pictures we got—of projected images made not with any lens at all, but merely via a tiny hole in a sheet of plastic—were amazing.

|

|

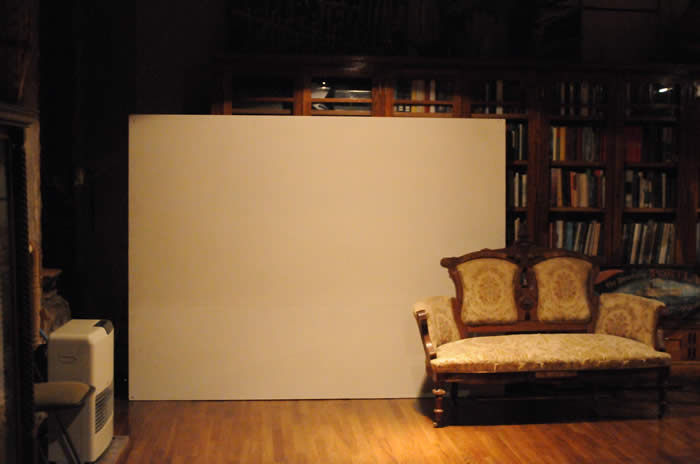

| Top: scene inside our "chamber," with white flat and sofa as a reference point. Bottom: From virtually identical camera position, early effort, under grey skies, produced a remarkably detailed, if somewhat monchromatic, image of downtown Eastport. (Frank Van Riper) |

The day had dawned overcast, threatening rain, but later grew sunny. In fact this was fine since it allowed us to see how the increasing brightness outside greatly affected the camera obscura images inside. Leslie’s and my first shots were dark and dramatic, but they were almost all monochrome—you would have thought we were working in black and white. By the end of the session the sunnier projected images were striking for their color and detail.

Here was the city of Eastport—including long vistas extending down the main street--squeezed through a less-than-dime-sized hole containing nothing but air and showing up beautifully on the big white flat that we used as our “canvas.”

|

|

| Some final money shots by Leslie after the sun finally came out. Note great detail in leaves in top image. Bottom image simply knocks me out. Remember: image on flat was made with NO LENS, just a tiny hole in plastic. [Note too: Bottom image has been turned upside down.] (Leslie Bowman) |

For my images, I deliberately cranked my ISO beyond the D300’s maximum of 3200 and kept my aperture wide open. I did this, not only to keep my exposures

comparatively short (60-80 seconds), but also because I was using my traveling Gitzo tripod that was not nearly as stable for long exposures as the big Gitzo I normally use.

From the very first images we made, this project was fascinating. I only can imagine how Vermeer felt when he first beheld this miracle of perspective-in-a-box.

And I could imagine as well how the camera obscura fired the creative imagination of pioneers like Louis Daguerre and William Henry Fox Talbot who, starting in 1839, began the arduous process of taking the principle of the camera obscura and—adding optical lenses and light-sensitive emulsions—transformed the evanescent pictures of the “dark chamber” into the permanent images of what came to be called “writing with light”—photography.

Frank Van Riper Fall/Winter classes,

field trips, Glen Echo Park, Md.

Great Portraits with Simple Lighting ($275)

Class 1: Thursday, October 29-Novmber 19, 7-10:30pm

Class 2: Thursday, January 21-February 11, 7-10:30pm

Achieve studio-quality results with equipment as simple as a flashlight, aluminum foil and a toilet paper tube. A great way to learn the basics and have fun doing it.

National Gallery, East Wing, Field Trip ($150)

Sunday, January 17

Spend the day photographing in one of Washington's great spaces, where opportunities for landscape, abstract and portrait photography abound. There will be an orientation session about a week before, followed by a potluck dinner and critique at Frank's home after the field trip.

For information contact: GVR@GVRphoto.com or go to www.glenechopark.org

|

Spend a week of hands-on learning and location photography with award-winning husband and wife photographer-authors Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman. Working from their stunning home in west Lubec overlooking Morrison Cove, (see photo above) Frank and Judy will cover basics of portraiture, landscape and documentary photography during morning instruction, followed by assignments in multiple locations including Quoddy Head State Park, Campobello Island, NB and the colorful town of Lubec itself. Daily critiques and one-on-one instruction. NO entrance requirement. Minimum age for attendance is 16. Maximum number of students each week is six . Students supply their own digital camera.

Read more about the Workshops in Frank’s column:

http://talkingphotography.com/archive/2009/photowork.htm

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based photographer, journalist and author. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. Among others, he is the author of the biography Glenn: The Astronaut Who Would Be President, as well as the photography books Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart. His book Talking Photography is a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over the past decade. His latest book (done in collaboration with his wife and partner Judith Goodman) is Serenissima: Venice in Winter. Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 8/09]

|