Go Back to current column

Lubec Photo Workshops – Summer, 2011 (see below)

Basics in Paradise

learning (and re-learning) during a Maine summer

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

On one glorious mid-August Saturday in Maine this year, I spent a fair amount of time in the hammock.

I was resting up from an exhilarating--if also exhausting—final week of workshop teaching: the third such photography workshop that my wife Judy and I taught this past summer through the famed SummerKeys Music school in Lubec, Maine, the easternmost town in the America’s easternmost state. (www.SummerKeys.com)

All three week-long classes (as well as a private three-day session with a mother and son) had great chemistry. All classes, too, had students at seemingly opposite ends of the learning curve. This also was true in the class with the mother and son. (As one might guess, tech-savvy Zach, 17, took to his camera’s electronic bells and whistles much more quickly than did his mom Susan. Each, happily, wound up making great photos—as did every one of the other seventeen photographers taking our workshops this summer.)

|

| Zach Teicher literally ran with this assignment: with his camera on tripod, set for long exposure, he ran to the gravestones and pointed flashlight at camera. Staying in motion rendered him invisible. (c) Zach Teicher |

For the novices (those who could not tell “an f-stop from a bus stop,” as one noted) the drill during the week was fairly clear-cut: a gentle, but firm repetition of the basics of good exposure coupled with a tough-love regimen that never once let anyone use his or her camera in anything but full-manual mode. This was like learning to drive by first mastering a stick-shift: you simply have more control of your machine, whether photographic or automotive, by working this way. In photography, this also means that you are not letting your camera do your thinking for you.

Judy and I also nixed all but the most basic post-production tweaking of digital images. This was, after all, a class in learning to see and record light correctly the first time--not in trying to make up for careless mistakes by relying on Photoshop after the fact.

|

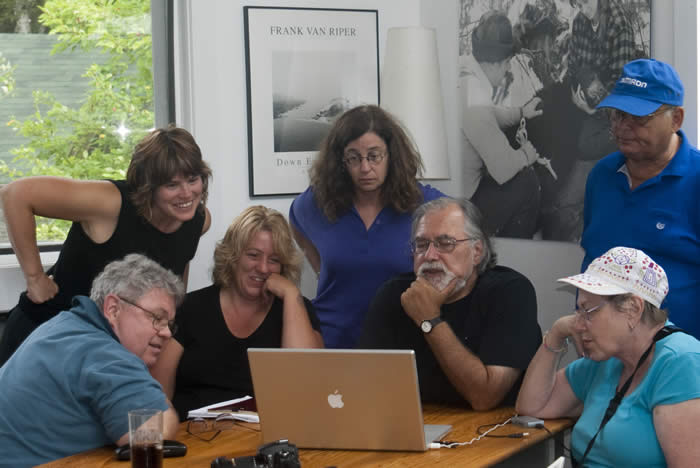

| Going over student work at our home in Lubec. (c) Fred Keeney |

But what became most obvious with each week of class was how even the more advanced students (as well as Judy and me) could benefit from going over our own set of basics—in much the same way that a musician will practice scales and finger exercises.

While Judy and I might not have to remind ourselves that f.22 is a much smaller aperture than f.2.8, or that a higher shutter speed is achieved through a much smaller fraction of time, like our students we benefited from conscious exercise: the simple act of bracketing exposures or trying myriad different camera positions and perspectives while shooting the same subject. Almost always it led to pleasant surprises and better pictures.

It’s all about practice. As veteran photographer Jay Maisel said: “to be a photographer, you must photograph every day.”

Or put another way: a good photographer never takes an image for granted, regardless of his or her level of experience or expertise.

The parallel between photographers and musicians was not difficult to draw, given our circumstances.

As longtime summer residents of Lubec and now as members of the SummerKeys faculty (the school handles our bookings in Maine), we have the advantage of knowing virtually all of the world-class musicians who teach there, in the tranquil confines of Down East. Where during the rest of the year in cities like New York or Philadelphia Judy and I could pay good money to hear a piano virtuoso like Charles Jones, or a flute master like Eve Friedman or a brilliant cellist like Joachim Woitun, or a viola star like Margaret Hjaltested, in Lubec we greet them on the street like the old friends they have become. Even better, we get to hear them perform during free concerts given every week by SummerKeys faculty in the gorgeous Congregational church at the top of Main Street.

This closeness, in turn, has given us—and our students—access to these and other musicians’ workshops and private classes, allowing us to make wonderful portraits and studies of musicians at work.

|

|

| Two workshops; two views. Top shows two students covering a music class from every angle. In later workshop student made clever use of in-camera multiple exposure (not PhotoShop) to record this view as it happened. Top: (c) Frank Van Riper Bottom: (c) Marvin Sirkis |

During these classes it became clear how important it was for musicians to hone and preserve their basic skills. Virtually no class we photographed, regardless of instrument, began without practice exercises: scales, fingering, etc. Even those classes with no mechanical instruments—Jack Ferguson’s voice classes, for example—began with important warm-ups and scales.

In the age of digital photography there is a tendency, I believe, to rely too heavily on electronics and post-production magic to make up for time we should spend practicing—or at least thinking about what we are photographing. Too often digital lets us shoot quickly and ask questions later. Even those shooting in manual mode with a digital camera do not face the necessity of having to re-load after every 36 shots, especially if they are using, say, an eight- or sixteen-gig memory card.

Don’t miss the old film days and having to reload every 36-shots? I must admit it does not bother me when I am shooting digitally at a big event or a wedding. But having to think about how many arrows remain in my quiver when I am doing my own work, shooting black and white film in my Leicas, forces me to slow down and actually think about what I am shooting and how I am shooting it. It’s a subtle thing, but a good thing, and it improves my photography. Another example: several years ago I was a guest lecturer during the Missouri Photo Workshop’s intense week of under-the-gun documentary photography during which participants had to arrive cold in a small Missouri town, come up with individual picture story ideas, sell them to a tough panel of veteran professional photo editors—then shoot the stories of course, beautifully and eloquently, all within the week. The rub was that each student was limited to shooting a set number of images—400, if memory serves—or the equivalent of about ten rolls of film.

And any discarded images counted against a student’s final total.

Talk about forcing you to think before you shoot.

It may be worth remembering, too, that our photographic forebears, up to and including news photographers who worked with 4x5 Speed Graphics, or medium-format Rolleis, rarely left for an assignment with much more than 15 or 20 unexposed pictures in bulky film holders (or 12 pix each on a roll of 120 film.) They had to think about every shot before they made it. [Let me concede here that, in tabloid news shooting especially, a comparative lack of film often led to stagey, formulaic images, but the overall point, I believe, still holds. Motordives and huge memory cards do not make better photographers; only ones who at the end of the day have more bad pictures to dump.]

Ironically, digital’s own speed and immediacy can—and should—let a photographer slow down and make sure that he or she is getting it right. During our workshops, Judy repeatedly preached this gospel, urging students to forego the motordrive mentality of “l’ll shoot 50 to get one good one.”

|

| Returning workshop student Frank Korahais made this gorgeous view in Lubec harbor by waiting for precisely the right moment. (c) Frank Korahais |

Take a test picture then work from there, Judy would say, urging students to improve exposure and composition slowly, incrementally—using the camera’s internal exposure meter--until the right mix was achieved. [See Judy’s primer on basics below.] Oftentimes, the best picture would not be the one made at the ‘perfect’ exposure, but the one that was slightly over- or under-exposed. That’s the real gift that digital gives us: the ability to see exactly what we are getting at the moment of creation.

Why squander such a gift on profligate, unnecessary shooting? Slower is better.

Another great thing about workshops like these is the leveling effect of everyone being in the same emotional, if not artistic or technical, boat--and the great relief of not having to please a boss, or an art director or a client. Sure, Ellen might not know an f-stop from a bus stop (by the end of the week she did) and Fred might be a terrific shooter who does great portraits as well as promotional shots of equipment for his company. But each had a need to learn. If Ellen needed to master the basics of exposure, Fred wanted to master the basics of freelance event and wedding shooting—of getting out on his own as a freelance photographer.

In our own way, Judy and I were able to help them both. And, if in the process we and the rest of our students also shot a newborn calf on a farm, made eerie and gorgeous nighttime images at the local cemetery, photographed in the fog at Eastport, and documented a traveling circus putting up its big top in Whitneyville—well, who said a workshop couldn’t also be fun?

|

|

Echo, a newborn calf, was an irresistible subject for us at nearby Tide Mill Farm. (c) Carla Beaton. Circus big top going up also provided a dramatic photo op. (c) Frank Van Riper

|

Basic Exposure Hints

By Judith Goodman

Four things to check before making a photograph: ISO, aperture, shutter speed and white balance.

- Check ISO (light gathering capacity)

--Lower ISO numbers are for brighter situations (eg: ISO 200 for sunny days)

--Higher numbers for less light (400 for shade; 800 for dark days; 1600 for indoors if you are not next to a window)

- Aperture and shutter speed are fractions!!

Aperture is the lens opening that allows in light. A smaller opening lets in less light and concentrates sharpness (depth of field)

f.16 is a smaller opening than f. 4 or f. 5.6 because these numbers represent fractions, not whole numbers

- Shutter speed is also a fraction

1/250th will stop action. The shutter is open for just 1/250th of a second so less light can come in.

1/4th of a second will let in more light over a longer period of time and allow things to blur—no stop action.

If you are photographing something that doesn’t move you probably can keep the camera still at 1/60th of a second, and certainly at 1/125th of a second.

If your subject is moving try 1/125th or 1/250th to stop action.

If you are using flash it will probably stop action if you are indoors.

Look at your first picture to decide if the color it’s true—you especially don’t want people to be blue--it’s a bad skin tone.

Average White Balance (“AWB” or “A”) works fine about ¾ of the time. If it doesn’t work try other settings even if they seem wrong. Remember, it’s the photo that counts. (NB: see manual for the more involved procedure for setting a custom white balance.)

Do not worry about composition until you get used to making correct exposures!

[NOTE: Do you have any other helpful hints for beginners?? Send them along and we will print them. Thanks.]

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys – Summer, 2011

Next summer, Judy and I will once again be teaching three hands-on photography workshops in Lubec Maine, sponsored by the SummerKeys Music school. (www.summerkeys.com)

Our dates for summer 2011will be as follows:

July 11th through 15th

July 25th through 29th

August 8th through 12th

Classes are limited to only six participants each week. Each class includes personal instruction, ongoing portfolio review and a wide range of location photography, including portraiture, landscape and night shooting. Each week’s class ends with a slide show of students’ best work that is open to the public.

Since their inception in 2009, Judy and I have tried to make our workshops a simpatico experience for all, regardless of skill level. There are no entrance requirements—all you need is a digital camera capable of manual operation and a desire to make pictures in one of the most beautiful areas of the country.

Watch the SummerKeys website www.SummerKeys.com for registration information, further details and pricing. Or contact us directly at GVR@GVRphoto.com

We look forward to hearing from you and to seeing you in Lubec!

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. His photography books include Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart, and Talking Photography, a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over ten years. His latest book (done in collaboration with his wife and partner Judith Goodman) is Serenissima: Venice in Winter www.veniceinwinter.com

Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 9/10]

|