Pre-publication notice: 2016 Maine photo workshop dates!

(see below)

A Reborn, Revitalized, East Wing

Photographing two icons in transition in Washington

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

One Sunday last June, shortly before my wife Judy and I and our three cats set off for Maine and a summer of workshop teaching (for us, not the cats) I led one of my favorite one-day photo workshops: at the East Wing of Washington’s National Gallery of Art.

I schedule this one-day class on a Sunday for a very important reason: downtown Washington on Sunday morning, even in the spring, tends to be bereft of tourists. This means that—for once—it’s a cinch to park free just steps from the museum.

And the National Gallery, especially the airy East Wing, affords excellent and varied vantage points for people photography, abstracts involving works of art, architectural shots, etc.--all possible rain or shine.

|

| Architect I.M. Pei designed this museum masterpiece on a difficult triangular lot. It is now a national treasure. Credit: Matthew Bisanz |

This particular Sunday not only produced great photos, it gave my students and me a look at the remarkable transformation that the East Wing is undergoing—one that will greatly expand this already glorious space to make it even more user-friendly. In addition, we were able to see and photograph two of my favorite sculptures in the world in transition: Henry Moore’s “Knife Edge Mirror Two Piece” literally hours after this huge outdoor sculpture at the front of the building had undergone a major cleaning; and Alberto Giacometti’s enigmatic, arresting “Walking Man” in a solitary setting that gave us virtually unfettered access to the masterpiece.

The experience gave me and my two students Sandy and Harriette a chance to use different exposure (and overexposure) to best render the artwork—as well as to explore unusual angles and camera position—with occasional judicious use of flash.

Of the many jewels that the nation’s capital displays to its visitors—the Capitol Building and the Air and Space Museum, to name two of the most popular—the East and West Wings of the National Gallery of Art are to me among the crown jewels. These two spaces, linked by an elaborate underground passage that itself is a must-see, house some of the finest artwork on the planet, from old masters to modern.

Not only that, but admission is free and handheld photography is permitted almost everywhere.

|

| Guide talks about the great Alexander Calder Mobile up above as kids in tour group check it out. © Frank Van Riper |

So it was a no-brainer for me years ago to inaugurate one-day photo workshops there through Glen Echo PhotoWorks, where I have taught for more than a decade. [nb: my next East Wing Workshop will be Sunday, December 20th. Go to the Photoworks website for more information when it becomes available: http://glenechophotoworks.org ]

Designed by the great I. M. Pei and completed in 1978, the East Wing immediately became a DC icon for its knife-edge exterior walls of Tennessee pink marble and for its huge elegant atrium dominated by one of Alexander Calder’s most famous mobiles, “Untitled, 1976.”

The space fairly shouts photo opportunity with its many levels and angles. And befitting a museum catering to contemporary work, the space is ever-changing. For example some years ago a sedate Japanese-inspired sand and rock garden beyond one long glass exterior wall gave way to an inside-outside collection of hand-assembled (and oh-so-photographable) dry-wall domes by the British sculptor Andy Goldsworthy.

Before the workshop I was concerned that the new construction might hamper us and limit our access and photography. But the Gallery’s head of PR Deborah Ziska assured me that there would be plenty to shoot. And she was right.

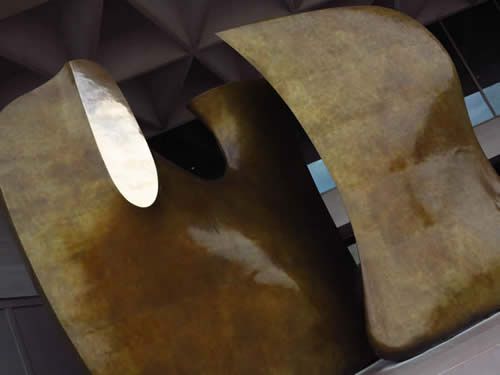

I could not believe how gorgeous the Moore sculpture looked when I pulled up outside the East Wing on June 7th. Just days before, as I drove past on a scouting mission, the great piece was encased in scaffolding as conservators busied themselves. Now “Knife Edge” looked reborn--bronze, golden and gleaming.

|

| Britsh sculptor Henry Moore's monumental piece at the entranceway to the East Wing has never looked better, after the work of a team of conservators. © Frank Van Riper |

Katherine May, Object Conservator at the National Gallery, reminded me that the sculpture was commissioned for the opening of the East Building, and was installed in May 1978, just before the new building opened. “The sculpture was cast and fabricated in England under a very tight deadline, and has had a long and complicated condition history, due not only to the harsh environmental conditions present at the entrance to the East Building, but also to the poor quality of the sculpture’s fabrication.”

She noted that in this case, “the sculpture was washed to remove deposited dirt, grime, pollution, and biological materials; and then a protective coating was applied to all surfaces and buffed with mechanical buffers.

“In 2014, a major conservation treatment to re-patinate ‘Knife Edge Mirror Two Piece’ was performed. In the late 2000’s, the patinated surface began to darken significantly and to become opaque and uneven. Planning for a treatment that would return the surface to the transparent golden patina intended by Moore began in 2012.”

It was a pleasure to circle this great sculpture and make photographs as we waited for the Gallery to open. Once inside Harriette, Sandy and I wandered freely, barely aware of the new construction that will add more than 12,000 square feet of exhibition space including an outdoor sculpture terrace overlooking Pennsylvania Avenue and two flanking sky-lit interior Tower Galleries.

It was when we looked up—and away from the great Calder Mobile—that I caught my breath. There, in splendid isolation on the East Wing’s Upper Level Bridge linking two galleries, was Alberto Giacometti’s “Walking Man” seemingly waiting for us to come up and commune with him.

|

| An icon of 20th century sculpture, Giacometti's "Walking Man" was there just waiting for us to photograph him. © Frank Van Riper |

This gaunt sculpture, appearing to walk resolutely to who-knows-where, has become a symbol of post World War 2 societal angst. The Swiss-born Giacometti (1907-1966), whose own thin figure seemed to ape his sculpture, never said this in so many words, but he once observed: "Emptiness filters through everywhere; each creature secretes his own void.”

The sculpture’s rough-hewn features and bent-forward attitude seemed to me to mix equal parts desolation and determination. I had admired this work for years, but today—standing by itself on the bridge—it shouted to be photographed. Sandy, Harriette and I spent the better part of an hour photographing it. We were close enough to touch it; we were all alone. Maybe a guard happened by--if so we did not notice. There were no other visitors on the bridge with us. We had ”Walking Man” to ourselves as if we owned it. And, photographically anyway, we did.

|

| Uncluttered background gave us a great way to photograph this masterpiece. © Harriette Fox |

We had one advantage this time: there likely were no other visitors on the bridge because, in effect, it led to nowhere. The far gallery was closed as part of the East Wing construction and its wide entranceway was closed off with grey-painted plywood and a small doorway.

Which was fine for us since it merely gave the sculpture an uncluttered background against which we could shoot.

Given such access, we turned Walking Man into an uncomplaining portrait subject. If I was taken with the sculpture’s rough-hewn features, Sandy and Harriette made multiple environmental shots. Sandy, in fact, made one of the best: slightly below the bridge and at an angle, as if to illustrate Walking Man’s Sisyphean upward struggle.

|

| Of all the photos of this work I have seen, this is the only one that imbues the figure with a real sense of motion. © Sandy Sugawara |

Because we could get so close to the sculpture, I wanted to make some details of Walking Man’s angular face. Virtually all of the photos I ever had seen of the piece had been full figure and seemingly made by available light—or at least with very little added light--with the figure in comparative darkness. So I tried a series of profiles, using various intensities of flash, until I got what I liked, incorporating the Gallery’s windows in the background, at an exposure that also allowed the trees beyond the windows to register and not blow out.

|

| Low-power flash brought up the craggy detail in the sculpture's face while the exposure was fast enough to render outdoor detail with no post-production manipulation. © Frank Van Riper |

But I was not satisfied. For years I had looked at this masterpiece but never had been able to really see, much less make a picture of, its face. Having all the time in the world—it was just the three of us and the sculpture, remember—I decided to break the rules for good exposure and see what I got when I overexposed Walking Man’s Face by a good couple of stops, letting the background simply wash out.

The result was revelatory. Visible for the first time were Walking Man’s hollow eyes and thousand-mile stare. Is that a cigarette in his mouth?

It was as if I were seeing the sculpture for the first time, and it only increased my admiration for Giacometti and his masterpiece.

Finally, I felt, I knew the Walking Man.

|

| In all the years I had admired this sculpture, I never saw it face to face. Until now. © Frank Van Riper |

-----

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, Lubec, Maine -- Summer, 2016

Daunted by Rockport??

Spend a week of hands-on learning and location photography with award-winning husband and wife photographer-authors Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman. Frank and Judy will cover portraiture, landscape and documentary photography during morning instruction, followed by assignments in multiple locations including Quoddy Head State Park, Campobello Island, NB and the colorful town of Lubec itself. Daily critiques and one-on-one instruction. NO entrance requirement. Minimum age for attendance is 16. Maximum number of students each week is nine. Students supply their own digital camera.

The Lubec Photo Workshops debuted in 2009 and were a huge success for their low-key, no-pressure atmosphere. Classes fill early.

2016 workshop dates are: July 25-27; August 1-5; August 15-19.

Tuition payable through the SummerKeys Music Workshops: www.SummerKeys.com

Or contact us: GVR@GVRphoto.com

NEW FOR 2016: Master Photo Classes with Frank Van Riper

These intense, three-day, limited enrollment classes are aimed at the more advanced student, who already has taken a photo workshop and who is familiar with basic flash. Max. class size: 3-4 students. Daily personal critique; includes on and off-camera flash instruction, location portraiture, night photography and more.

Enrollment must be approved by the SummerKeys director.

Dates: July 25-27; August 8-10. See the SummerKeys website for details.

Come photograph in one of the most beautiful spots on earth!

-----------------

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 8/15]

|