Pre-publication notice: 2016 Maine photo workshop dates!

(see below)

"Irving Penn - Beyond Beauty"

A master gets his due--and one dumb slam

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

Decades ago, Irving Penn got me with the cigarette butts.

It was in Manhattan in the 70s—whether at a gallery or a museum, I don’t recall, though MoMA is a good bet—and there on the walls were huge platinum prints of studio-lit street detritus, including cigarette butts.

The sheer monumentalism of the images was riveting, the words “Camel” and “Chesterfield” on each butt so large that I could discern their different type fonts.

|

| The butts on the wall at SAAM are smaller than the ones I saw a quarter century ago in New York, but the graphic effect is the same. |

The photographs were in black and white—each a four-section assemblage of platinum prints, maybe three feet by four feet--and they were an equally huge remove from anything I ever had seen before, much less photographed.

Bluntly, Irving Penn was re-interpreting my visual world by showing me street garbage writ large. And I am grateful I had the sense to realize this because it helped form me as a photographer. One of our jobs is to show things that have not been seen before, or at least re-interpret them with our own stamp and creativity.

Irving Penn (1917-2009) did this so well and so often that I once called him one of photography’s true Renaissance men. “Irving Penn: Beyond Beauty,” the current retrospective of his work at the Smithsonian American Art Museum (through March 20th) offers a quietly elegant overview of his long, long career, and points up especially Penn’s genius as a portraitist, both of people and of things.

|

| Entrance to the elegant Irving Penn retrospective at the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Exhibit photos © Frank Van Riper |

He was perhaps best known for his meticulous fashion photography—he was obsessive about every detail, much as an old master painter might have obsessed over still lifes. Obviously, as with the cigarettes, he could turn the mundane into the magical—even including bricks of frozen food. In fact, Irving Penn is one reason I never take closeup pictures of flowers anymore: his studio studies of parrot tulips, beautifully cross-lit and taken on a clear white surface, made me realize years ago that I never could do better.

|

| "Frozen Foods," New York, 1977. Penn's artistic eye for composition is obvious in this very cold still life. Note, too, how the studio lighting emphasizes shape and contour. All Penn images © The Irving Penn Foundation |

He pioneered—as did his contemporary Richard Avedon—starkly lit, gorgeously printed, black and white celebrity portraiture. While some of his portraits might seem aloof, lacking the yeasty immediacy, and at times supremely uncomfortable closeness, of an Avedon image, the majority of them are telling and arresting renderings of faces we have come to know, though not like this.

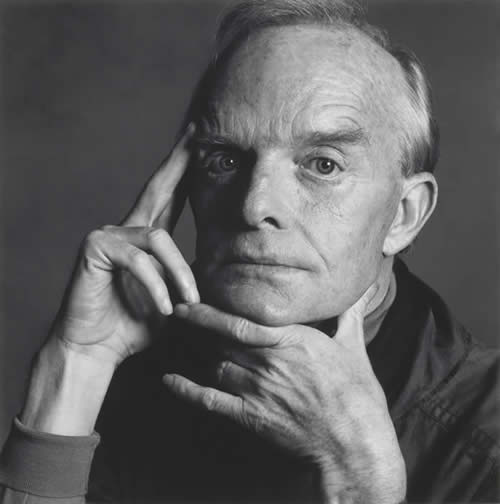

In 1965, for example, a nattily dressed Truman Capote poses with his eyes closed, his skin sleek, his hands caressing his face. Just fourteen years later, in 1979, Capote, now ravaged by drug abuse and the liver cancer that would kill him in five years, stares into the camera: a virtual death’s head.

|

| "Truman Capote," New York, 1979. Made five years before the author's death from liver cancer and drug abuse, the portrait is at once riveting and cautionary. |

To be sure, Penn was a control freak—and as such felt most in control in the studio or working on location under studio conditions. He was not, for example, a great environmental portraitist like Arnold Newman, or later, Neil Selkirk or Mark Seliger. But his studio work often was beyond compare—even in his bread-and-butter work for Revlon: his now-iconic still lifes of Clinique cosmetics, which are not part of this show at the request of the Penn estate.

In a rare bit of humor in the exhibition, Curator Merry Foresta shows the test shot for a large 1947 studio portrait that would feature nearly two dozen of the top Broadway producers of the post World War 2 era. In the test shot, Penn sits all by himself in the center of the set: scaffolding hung with loose fabric, a lone skull (presumably Yorick’s) sitting on the top row of makeshift seating.

Given this stark setting, it must have been a bear to fit all that talent—and ego—into one coherent portrait (and to show everyone at his or her best) but Penn did it. He also included Yorick, along with Leland Hayward, Irene Selznick and Rodgers & Hammerstein, among others.

The SAAM show features rarely seen images including Penn’s early street photography that is competent, sometimes compelling, but ultimately derivative, as well as masterly portraits of fashion models in the haut-est of couture, made shortly before his death in 2009 at age 92.

|

|

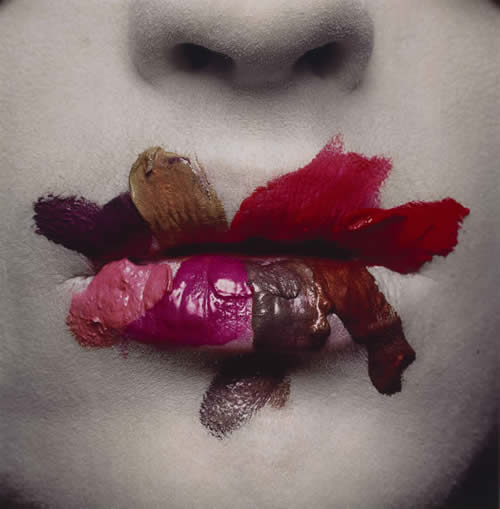

A photographer's growth over decades. Top image, made in the south in 1941, is no better or worse than those made by Walker Evans, Eugene Atget, Berenice Abbott, etc.-- i.e.: good but not original. But only Irving Penn could have made "Mouth (for L'Oreal)" in 1986. |

Irving Penn died doing what he loved. We all should be so lucky.

Not so fortunate was a recent Washington Post review of this show, and of Penn’s career, bluntly dismissing Penn as someone who “squander[ed] his talent in fashion and magazines,” and dismissing his portraiture as “virtuoso exercises in the scrupulously dull.”

This is not the first time the Post has published critical drivel. A dozen years ago, its previous art critic excoriated David Hockney's revelatory book Secret Knowledge, that convincingly theorized that optical tools had been used by artists centuries earlier than once had been thought. The critic’s review of this book seemed to me a willful mix of ignorance and bile--and I said as much in this space.

Both these slams were filled with the arrogant artspeak and smug pronouncements that come from gifted academics who write about art but who never themselves have worked as artists, especially in a particular medium, in this case photography. It makes me appreciate why many artists simply do not read any reviews at all. Too often critics have little to say, much of it wrong.

[A personal note: some 25 years ago, when I was a photographer member of Touchstone Gallery in Washington, DC, I was asked to help edit and produce a small tabloid called “EyeWash.” The concept was simple: artists would write reviews of other artist’s shows. An invitation to mutual back-scratching or back-stabbing, one might think. Only it did not turn out that way. In most cases, the reviews were thoughtful, and supportively critical—the reviewers had been in the trenches and knew what it was like to be a working artist. It showed in their writing.]

Irving Penn grew up in middle class comfort and was favored by luck. But neither would have done him much good if he did not also have talent. [Young Irving, by the way, was not a sport of nature; his younger brother Arthur Penn was the acclaimed director of groundbreaking movies like “Bonnie and Clyde,” “Mickey One” and “The Miracle Worker.”]

Luck favored Penn when he studied art and industrial design under Alexey Brodovitch in Philadelphia in the late 1930s. Brodovitch, a volatile but brilliant Russian émigré, was the art director at Harper’s Bazaar and recognized Penn’s talent, first as an artist. Their professional partnership flourished as Penn gravitated to photography, and luck favored Penn once more when Alexander Liberman, another iconic art director of the time—hired Penn as a photographer for Vogue.

|

| "Woman in Moroccan Palace (Lisa Fonssagrives-Penn)" Irving Penn met his future wife during a fashion shoot and quickly fell in love. They were married for 40 yers, until her death at age 80. |

Penn himself was a quiet-spoken, even reticent, man who married one of the most beautiful women in the world and stayed married to her for more than 40 years until her death at age 80. (He met model Lisa Fonssagrives during a fashion shoot. In this case, the rest really was history.)

Elizabeth Broun, director of the SAAM, recalled one odd, poignant, episode shortly after Lisa’s death, when she met Penn for lunch in Manhattan at the Union Square Café. She was there to get to know Penn better and also in hopes of expanding the museum’s collection of Penn’s work.

“He was still grieving for Lisa,” Betsy Broun recalled, and when she sat down with Penn he drifted in and out of fond reminiscences, wanting to talk.

When the time came to order, she told the master, “I’m going to order what you’re having.”

“I’m just having the mashed potatoes,” Penn replied.

“So there I was, with a tureen of mashed potatoes” for lunch.

Penn was a gentleman, a genius and a great photographer.

“He also was just a strange guy.”

-----

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, Lubec, Maine -- Summer, 2016

Daunted by Rockport??

Spend a week of hands-on learning and location photography with award-winning husband and wife photographer-authors Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman. Frank and Judy will cover portraiture, landscape and documentary photography during morning instruction, followed by assignments in multiple locations including Quoddy Head State Park, Campobello Island, NB and the colorful town of Lubec itself. Daily critiques and one-on-one instruction. NO entrance requirement. Minimum age for attendance is 16. Maximum number of students each week is nine. Students supply their own digital camera.

The Lubec Photo Workshops debuted in 2009 and were a huge success for their low-key, no-pressure atmosphere. Classes fill early.

2016 workshop dates: July 18-22; August 1-5; August 15-19.

Tuition payable through the SummerKeys Music Workshops: www.SummerKeys.com

Or contact us: GVR@GVRphoto.com

NEW FOR 2016: Master Photo Classes with Frank Van Riper

These intense, three-day, limited enrollment classes are aimed at the more advanced student, who already has taken a photo workshop and who is familiar with basic flash. Max. class size: 3-4 students. Daily personal critique; includes on and off-camera flash instruction, location portraiture, night photography and more.

Enrollment must be approved by the SummerKeys director.

Dates: July 25-27; August 8-10. See the SummerKeys website for details.

Come photograph in one of the most beautiful spots on earth!

-----------------

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 11/15]

|