2017 Lubec photo workshops: dates just announced

(See below)

Manuello Paganelli's Cuba

Voyage of discovery by a not-quite-native son

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

Photographers can lay visual claim to places through heritage or compulsion. Cartier-Bresson’s Paris, for example, or Josef Koudelka’s Prague--or even Swiss-born Robert Frank’s America.

Thirty years ago, when my wife and I bought property in Lubec, Maine, the easternmost town in the United states, I felt compelled to chronicle the region in words and photographs. My 1998 book Down East Maine/A World Apart received wide acclaim—especially from locals--but no one ever mistook me for a native son.

But I am Italian—fully half, from my mother, the former Carmela Casullo. This informed my passion for Italy and helped produce Serenissima: Venice in Winter, a black and white love poem to the Floating City that I did in 2008 with my wife and professional partner Judith Goodman.

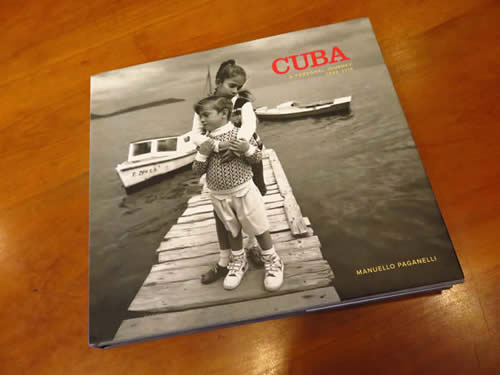

In the case of Manuello Paganelli, author of the stunning new book Cuba: A Personal Journey: 1989-2016 (Daylight Books) the twin forces of compulsion and heritage combined. There was no way Manuello could not have produced this work, and we are the richer for it. His book has special resonance now that Maximum Leader Fidel Castro has died, at age 90, and the world focuses anew on how and to what extent this tiny island will change, as seemingly it must.

|

Manuello Paganelli's book on Cuba was 25 years in the making and the product of numerous trips in search of long-lost relatives, like his two cousins pictured above on the book's cover. More than a family mission, Paganelli's book also chronicled Cuban life at a critical time. (All photos © Manuello Paganelli. All rights reserved.) |

I first met Manuello, now a 56-year-old documentary, editorial and commercial photographer based in California, decades ago when we both were beginning our careers as independent freelance photographers in Washington, DC. Manuello, a handsome Cuban/Italian (what’s not to love?) could light up a room with his enthusiasm and brio. And he brought that spirit to his work.

He loved to tell this story on himself: when he was starting out, and wanting to get guidance from his older, more accomplished, colleagues, he spotted a Darkroom Magazine cover story about Ansel Adams, arguably America’s, if not the world’s, greatest landscape photographer.

It was a simpler time then, and Paganelli just looked up Adams’ phone number in Carmel, California and called.

“Hello, I would like to speak with Ansel Adams,” Manuello told the person who answered the phone.

“Yes…”

“No, I mean Ansel Adams the photographer…”

“Yes…”

“No, I mean Ansel Adams the photographer who was on the cover of Darkroom Magazine…”

“Yes.”

Finally, it dawned on Manuello that he was talking to the great man himself. Adams then spent precious time on the phone talking to this eager wet-behind-the-lens photographer, giving him advice.

In the ensuing years. Paganelli built a strong reputation as a photojournalist and portraitist, assembling an international clientele that included Time, Der Spiegel, Businessweek, Sports illustrated, Life, Forbes, Newsweek, and many more. For much of that time, doing any kind of book took a back seat, as Manuello packed and unpacked his bags for every new assignment.

Subtly, however, Cuba beckoned. Though he had no childhood memories of Cuba (he was born in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic) his mother’s family came from Cuba. In the end it was work that finally drew him “home.”

|

|

| Two Cuban icons, Fidel (on the wall) and the late Che Guevara. Fidel's death, though expected, was a blow to older Cubanos who revered him. Bottom: portrait of a young girl who practices Santeria, holding a doll that is used in ceremonies that draw from many faiths and customs. |

“It really didn’t occur to me to publish a book during those early years or that it was going to take me more than 25 years to accomplish it,” Manuello noted a little ruefully in our email conversation. “The notion first entered my mind in the mid-90s, when many of my clients (e.g. Time, Forbes, Vibe) were already sending me on photo assignments to Cuba. They began encouraging me to put together a book after I had my first solo photo exhibit on Cuba in 1995 and had a great reception. I remember how strange it was, people looking at my work during the opening night and asking lots of questions since nobody knew anything about that nation.”

Strange and arresting indeed:

--A smiling bride in her white gown climbing into a lovingly cared for US car from the 50s

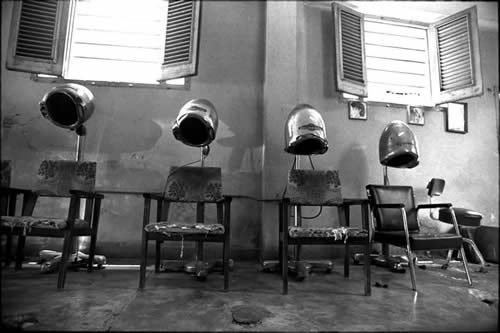

--A battered set of chairs at a hairdresser’s shop, fronting equally ancient equipment

--A haunting portrait of a young practioner of Santeria holding a doll used in ceremonies

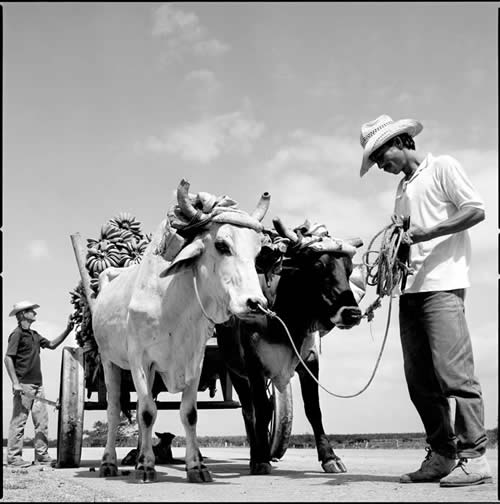

--Oxen and campesinos in the field

--The excitement of an illegal cock fight

--A dramatic closeup of an anguished religious pilgrim crawling on her stomach in supplication

--A nighttime aerial of old Havana, looking as it must have during the era of ‘Guys and Dolls’

|

|

| Havana wedding (top) shows smiling bride getting into a lovingly restored US car from the 50s. Well-worn chairs in beauty shop (below) under equipment from roughly the same era as the wedding car. |

For this personal photography, Manuello worked in black and white, in the manner of the great documentary shooters. He preferred his Leicas, as well as other film cameras, to create a uniform look on Kodak’s venerable Tri-X film.

Ultimately he partnered with New York art director Melanie McLaughlin and to their surprise found not one but two publishing houses that seemed willing to bankroll and publish a book of Manuello’s work, especially as US-Cuba relations thawed. But, as always happens in bigtime book publishing, there was a catch.

Skittish at the prospect of publishing a book in (horrors!) all black and white, both houses said in effect: “Great stuff, Manuello, but can you also sprinkle in a few color snaps so we can appeal to a wider market—kind of like National Geo?”

Not surprisingly, both deals fell through.

Ultimately, Paganelli hooked up with Daylight Books, a North Carolina non-profit devoted to printing serious top-tier photo books—albeit with a hefty infusion of cash from the artist. He also made good use of veteran photo editor Jim Colton's talents for editing and sequencing the book's images.

“I didn't have problems with the money and for sure I didn't want to have my first book published by companies like Blurb or some other online self-publishing company,” Manuello told me. [nb: I have to say, as a veteran of more than 30 years dealing with publishers, and with five books under my belt, the Daylight model very well may be the wave of the future.]

|

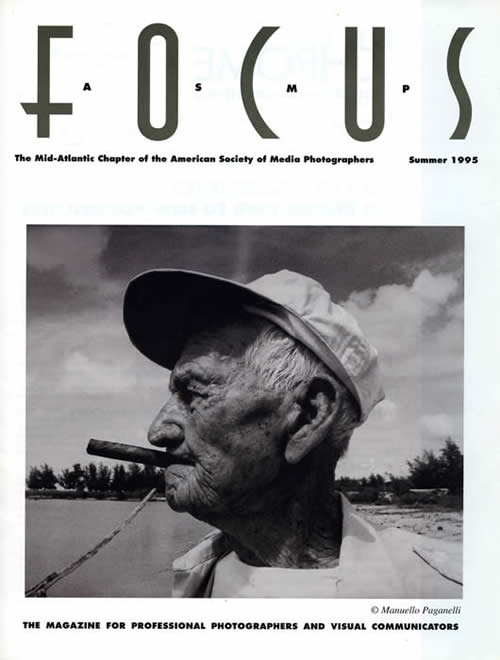

| When I was editor of this magazine I gave Manuello the cover in summer of '95. This Cuban fisherman was said to be one of the models for Hemingway's courageous lead character in 'The Old Man and the Sea.' |

Books like Cuba: A Personal Journey succeed (or fail) on the passion of the author, and Manuello’s passion for Cuba was obvious even in those early gallery images. [I first saw this in 1995, when I published a cover piece on his early Cuba work in a small magazine I was editing at the time.] It’s one thing to present first-rate photos, but--especially when documenting a place that for so long (to Americans anyway) has been virtually unknown—the text that accompanies those photos becomes all the more important, even vital. In Manuello’s case, he takes us on a years-long odyssey of discovery (looking for his Cuban relatives along the way) and offers wonderfully human insights and anecdotes that not only accompany his strong available light BxW images but create a synergy that makes his book more than the sum of its parts:

We are in the battered car as he rides through tortuous roads with friends searching for relatives, only to wind up in a ditch. We are there in the countryside when he is asked to make pictures at the wake of an ancient and revered mamacita—only to drop his flash into the coffin.

We are there on another road trip when he pretends to be a Cuban deaf-mute as he tries to circumvent the Castro-era laws forbidding foreigners to share rooms with locals.

And don’t get me started on the plague of tadpoles.

|

|

| Manuello Paganelli shot from ciudad to campo. Above: two sisters talk by an old US car under stark streetlight. Below: a team of oxen provides four-legged transportation for crops. |

Many otherwise passable photo books fail miserably here. Too often, what little text the photographer writes is self-important and self-indulgent. I could not care less about a shooter’s internal creative process, as in this turgid example from a recent photo book on Venice:

“I have walked through the streets and across the bridges for several days now: fatigue has become a travel companion who reminds me that I am no longer twenty years old. But it has not hindered the sharpness of my ’sixth sense’: I am always on the lookout for the slightest sensation. In fact, I look without looking. I wait for the sign, the magical instant that is impossible to describe: when it happens and it’s real, I begin to ‘fix’ on a certain area. From there I go into contemplation mode…”

By contrast, Manuello provides real information, real events—not surprising, since he not only is a photographer; he is a photojournalist used to telling stories with both photos and words:

“It was my fourth trip to the island, and I was determined to find my lost Cuban relatives,” Manuello writes, having only a decades-old, third-hand letter as his guide. “I recruited a couple of friends that I’d met on an earlier trip. In typical Cuban fashion, one friend knew a friend-of-a-friend who worked at the Civil Registry, and within a few days, the registrar pointed us to the town of Camaguey…”

The drive was awful—the weather and terrain terrible—and after seven hours the group was forced to seek shelter. But there was only a simple hotel for locals nearby, no hotel for foreigners (this mandatory segregation was the law during the Castro-era ‘Periodo Especial,’ and the fines for violating this prohibition were severe—up to and including prison time for Paganelli’s friends and, for Manuello, persona non grata status that would keep him from ever returning to Cuba.)

After changing into a friend’s extra shirt, the better to blend in as a local, “my friends told me to remain totally silent when we checked in; in fact they wanted me to pretend to be a deaf-mute.”

The hotel manager was skeptical when told that the silent person in front of him had forgotten his ID card. There followed a comic opera of faked sign language that finally seemed to mollify the official.

But then the manager’s superior appeared and said they should call the sign language teacher from the local school to clear things up once and for all. A lifetime passed as the phone call was made. Thankfully, there was no answer and the trio was allowed to spend the night, but not before another hotel worker said his wife knew sign language and could be at the hotel early the next morning

Needless to day, the three caballeros got the hell out of town before dawn.

|

| Contemporary view of Havana at night conjures up the days when Americans routinely vacationed there, gambling at Mafia-backed casinos, in the era of the Broadway hit 'Guys and Dolls.' |

Manuello did finally reconnect with long-lost cousins—and made wonderful photos of them. But this is much more than a family photo album. Having worked on this project so long, he is able to provide a multi-tiered look at Cuban life, from campo to ciudad—that includes both warts and triumphs.

The aforementioned “Periodo Especial,” for example, was especially difficult for many—food shortages saw every Cuban lose 20 pounds on average over this time—but, as Cuban diplomat Jose Luis Ponce Caraballo notes in the book, Cuba also could boast a system that provided not only universal health care, but free education (including college), as well as a society with no illiteracy, no “children begging in the streets” and schoolkids going to class “properly clothed in uniforms.”

Obviously, with the Obama administration having finally normalized relations with its southern neighbor—and now with the death of Fidel--the question arises: how will this affect the island nation, so long isolated from the US?

“The answer to that question may win you the lotto,” Manuello notes. “Cuba is in a very difficult predicament. By conversing with my relatives and many Cubans on the island the sentiment is that El Sistema, as most Cubans call the revolutionary government, will probably continue with some changes added here and there. Changes which we have witnessed, after Raul Castro [took over power from his ailing brother] loosened the law permitting citizens to buy and own private property. Then new economic reforms were enacted and things changed a bit further after Obama opened up the diplomatic talks over a year ago. [But] Fidel [was] much loved in Cuba, which may be difficult for Cubans in Miami or other places to grasp at all. So I don’t think that opening Cuba more to the free market will lead to a democratic leadership.”

What the thaw in US-Cuban relations will do, one hopes, is finally give Americans a chance to visit this remarkable place—as well as give a new generation of photographers the chance to follow in Manuello Paganelli’s very impressive footsteps.

[ For information on Manuello's photo workshops in Cuba, go to www.manuellopaganelli.com -- also follow him on Facebook:

facebook.com/manuello.paganelli and Instagram: Instagram.com/manuellopaganelli ]

-----

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, Lubec, Maine -- Summer, 2017 dates just announced...

Daunted by Rockport??

Spend a week of hands-on learning and location photography with award-winning husband and wife photographer-authors Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman. Frank and Judy will cover portraiture, landscape and documentary photography during morning instruction, followed by assignments in multiple locations including Quoddy Head State Park, Campobello Island, NB and the colorful town of Lubec itself. Daily critiques and one-on-one instruction. NO entrance requirement. Minimum age for attendance is 16. Maximum number of students each week is nine. Students supply their own digital camera.

The Lubec Photo Workshops debuted in 2009 and were a huge success for their low-key, no-pressure atmosphere. Note: Classes fill early.

2017 workshop dates: July 17-21; July 31-August 4; August 14-18.

Tuition payable through the SummerKeys Music Workshops: www.SummerKeys.com

Or contact us: GVR@GVRphoto.com

NEW: Master Photo Classes with Frank Van Riper

These intense, three-day, limited enrollment classes are aimed at the more advanced student, who already has taken a photo workshop and who is familiar with basic flash. With a maximum enrollment of just five, these classes are nearly half the size of our regular workshops. NB: last summer's Master Classes were fully booked almost immediately.

2017 Master Photo Class dates:July 24-26; August 21-23

Come photograph in one of the most beautiful spots on earth!

-----------

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 11/16]

|