Ross Barnett and the Shackles of Race

My Time as a Raisin in the Sun

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

“Let’s ask him!” someone in the all black crowd said 56 years ago—pointing at me, the only white face around.

I was there as a student reporter from the CCNY newspaper, covering a meeting of the Hamilton Grange, a neighborhood association near City College of New York, in the heart of Harlem. The Grange was not our regular beat, but this time, on a humid evening in May, 1964, tensions were high because of what was about to happen at the College.

In a spectacularly tone-deaf effort to “hear both sides,” the CCNY student government had invited one of the South’s most notorious segregationists, former Mississippi Gov. Ross Barnett, to the College’s Great Hall to address the student body on the then-pending civil rights bill that was by no means sure of passage during that tense and dangerous time in our history.

|

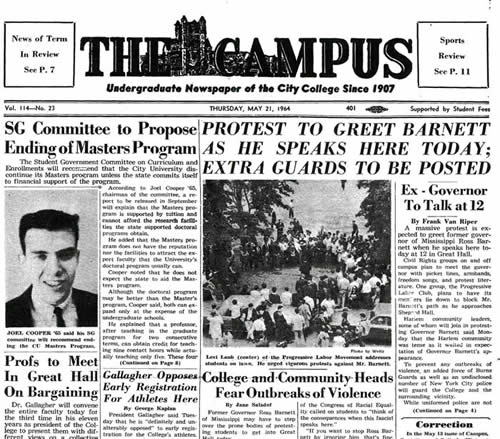

| In 1964 the CCNY Student Government decided to invite one of the most notorious segregationists in the country to apeak in the middle of Harlem on the pending Civil Rights Bill. What could go wrong? |

Any other school in any other part of the city might have pulled this off. But this was Harlem, for God’s sake—within blocks of the Apollo Theater, for God’s sake—and the people who lived there were not pleased that an outspoken segregationist was about to be welcomed into their midst.

And, involuntarily, I had to explain it to them.

Ross Barnett easily might have been the poster boy for white racism back then, along with Alabama’s George Corley Wallace. A dough-faced bigot whose father had fought in the Confederate army, Barnett ran for governor of Mississippi pledging never to integrate Mississippi schools. “The Negro is different because God made him different, to punish him,” Barnett once said. “His forehead slants back. His nose is different. His lips are different, and his color is sure different." He vowed to keep the races separate, promising never to ”drink from the cup of genocide.”

But that was not all. Barnett cemented his place in hell early in 1964—just months before his scheduled appearance at CCNY--when he interrupted the second Mississippi murder trial of Byron De La Beckwith, accused of assassinating black civil rights leader Medgar Evers, to shake hands with the defendant. Barnett’s showy entrance at the trial came as Evers’ widow, Myrlie Evers, was testifying. Beckwith, facing an all-white jury for the second time, managed to escape conviction once more. [Some three decades later, on the strength of new evidence, and new federally-mandated rules for jury selection, Beckwith finally was convicted by a mixed jury and sentenced to life without parole. He died in prison.]

Against this background, there I was—the opposite of the “raisin in the sun” in Langston Hughes’ poem--trying to explain the unexplainable to an angry and aggrieved African-American crowd at the Hamilton Grange.

I rattled on a bit about disagreeing with someone while defending his right to speak, not making any converts but at least getting a respectful hearing. But what happened after the meeting is what remained with me. I had been talking to a few folks out on the street when I was approached by a young black man who had been in the audience. He was tall, softspoken and not especially angry, though he could not fathom why CCNY would invite someone like Barnett to speak. Before we shook hands and parted, he pointed up toward St. Nicholas Terrace and my school and said with a moving intensity how he always had dreamed of going to "the college on the hill."

Suddenly, anything Ross Barnett might have had to say seemed trivial and small.

[For the record, Barnett showed up, had a few eggs tossed is way, did his racist dog and pony, then left without further incident.]

I’ve thought a lot of that evening at the Hamilton Grange, and about what that young man said, in the weeks following the murder-by-cop of George Floyd in Minneapolis and the national and international outrage that his killing has triggered. For all of the previous instances of police brutality against blacks in America, Floyd’s choking death, administered slowly, even calmly, by a white cop (who didn’t seem to care that he was being recorded on a smartphone) seems to have pushed most decent people past a tipping point.

This black man’s death, it finally seems, is going to matter.

|

| How do you define bravery? Like this. Magnum photographer Bruce Davidson documented the civil rights movement for four years, including this powerful image of a young black protestor in the South surrounded by taunting whites. © Bruce Davidson, from his book 'Time of Change -- Civil Right Photographs 1961-1965' |

Certainly, it has sparked soul-searching among whites of goodwill about their own attitudes on race.

For me it has made me more appreciative of, and grateful for, my own limited status as an outsider while growing up in New York, and for the equally limited ability it gave me (as, let’s face it, a privileged, educated white guy) to see the world through others’ eyes.

In the Bronx of my youth in the early 1950s, in a lower middle class Jewish neighborhood within blocks of Yankee Stadium, I (a half-Dutch, half-Italian Catholic) was the minority--not the Frieds or the Goldbergs or the Needles who were our neighbors. What few black kids my friends and I played with, and who were our classmates at PS 90, lived only a few blocks away, in walk-up tenements not much different from ours.

Years later at CCNY black students were a far larger cohort of the student body but the white population still was predominantly and, to me, familiarly, lower-income white and Jewish. But if the CCNY that I attended in the 1960s was a white island in a black community, it still was an island composed of outsiders. Born in 1847 as “The Free Academy,” City College was where minority and poorer students could get a first-rate college education for free. (“A kind of proletarian Harvard,” the New York Times once called it.) Though the City University now charges tuition at its colleges, including CCNY, it is nothing like tuition charged at, say, the other Harvard.

And with graduates like Colin Powell, Oscar Hijuelos, Mario Puzo, Felix Frankfurter, Jonas Salk, Paddy Chayefsky, Bernard Baruch and so many more—it was a hell of a return on the investment. And it continues to educate the poor and minorities. Over the years, the whiteness of the student body has changed: first with an influx of latino students, and in later years Asian. The ethnic makeup of the City’s student body now roughly mimics that of New York itself, with whites making up about a quarter of the population.

There long had been a closeness between African Americans and American Jews, though those ties have been subject, sadly, to strain and resentment. Each group once existed on the fringes of an American society that at one time was overwhelmingly white, anglo and Protestant. And though I never directly felt prejudice because of my Italian Catholic background, my mother, whose family had emigrated from impoverished southern Italy just decades earlier, always had an immigrant’s fear of angering people in authority.

New York then--as now--was, if not a melting pot, then at least a collection of different cultures and religions, not always mixing easily but at least coexisting.

That coexistence led to a certain smugness decades ago, especially as we watched the evening news and saw black and white civil rights marchers being set upon by dogs, club-wielding cops and doused by high-pressure fire hoses as they marched through the segregated South. Yet one thing that Ross Barnett said long ago still brings me up short. In the south, Barnett said, we don’t care how close blacks are to us as long as they don’t go higher. In the north, he maintained, blacks can go as high as they want--as long as they don’t get close.

There, from segregation’s poster boy, was the definition of northern white privilege.

|

|

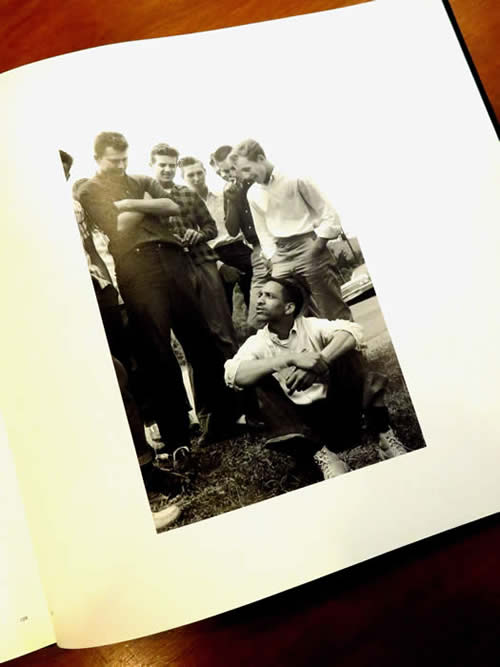

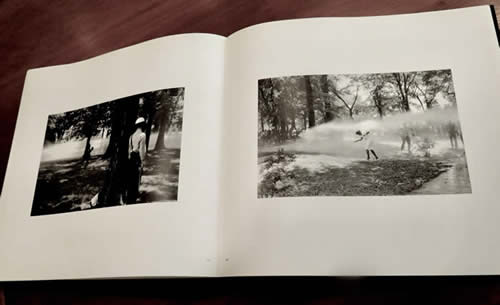

| (Top) High-pressure fire hoses were a favorite tool used against civil rights protestors in the segregated South of the 1960s. (Bottom) Woman protestor sits in police van after her arrest as white cop confiscates her posters. © Bruce Davidson. |

It’s all about distance. I can empathize all I want with those who feel injustice, but my white butt never will have to worry about being pulled over by a racist cop—and worrying that--Oh God—in reaching for my wallet he thinks I’ve got a gun.

I can sympathize with—and send money to—efforts to finally bring clean water to minority folks in Flint, Michigan—while enjoying my own clean water here in Washington, DC.

And I can think back to that time, when I was in college in New York, when other, braver, of my counterparts were joining the Freedom Riders down south--and marvel at a courage I never could imagine.

"It was a terrorist atmosphere," recalled famed Magnum photographer Bruce Davidson, who covered the civil rights movement on the ground and talked to me about it several years ago. Frightening, sure, he said, "but what replaced that terror was the dignity and patience of those marchers and demonstrators."

For Davidson personally the experience was dangerous up to a point--after all, he was white and he could get the hell out of Dodge whenever he felt like it and no one would have faulted him. But he kept dong it, over four long years. No, Davidson told me, "the real danger that counts is the danger of confronting your own prejudices.” Because of his intense, personal photo coverage, he said, “I began to feel very close to African Americans on an individual basis."

It’s the kind of experience that stays with you and changes you. Perhaps like the experience people like me are having, in the aftermath of the terrible death of George Floyd.

###

Bruce Davidson’s compelling portfolio of civil right images was published in 2002: ‘Time of Change--Civil Rights Photographs 1961-1965’

He has done many other books, and each is remarkable. Some of my favorites are ‘Brooklyn Gang,’ ‘Subway’ (in color), ‘East 100th Street,’ and ’Circus.’

-0-0-0-0-0-

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, Lubec, Maine -- Postponed by pandemic

Join us for another magical summer NEXT year--2021

Spend a week of hands-on learning and location photography with award-winning husband and wife photographer-authors Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman. Frank and Judy will cover portraiture, landscape and documentary photography during morning instruction, followed by assignments in multiple locations including Quoddy Head State Park, Campobello Island, NB and the colorful town of Lubec itself. Daily critiques and one-on-one instruction. NO entrance requirement. Minimum age for attendance is 16. Maximum number of students each week is nine. Students supply their own digital camera.

The Lubec Photo Workshops debuted in 2009 and were a huge success for their low-key, no-pressure atmosphere. Note: Classes fill early.

2021 workshop dates: To be announced

Tuition payable through the SummerKeys Music Workshops: www.SummerKeys.com

Or contact us: GVR@GVRphoto.com

NEW: Master Photo Classes with Frank Van Riper

These intense, three-day, limited enrollment classes are aimed at the more advanced student, who already has taken a photo workshop and who is familiar with basic flash. With a maximum enrollment of just five, these classes are nearly half the size of our regular workshops. NB: last summer's Master Classes were fully booked almost immediately.

2021 Master Photo Class dates:To be announced

Come photograph in one of the most beautiful spots on earth

-----------

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 6/20]

|