Think Developing Film was Hard?

John DiMartino's Love Affair with Tintypes

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

There may be more difficult ways of making photographs, but I can’t think of any.

In the 1870‘s photographers like William Henry Jackson and Carleton Watkins roamed the American southwest documenting the hills, mesas and mountains of that wide open space while also making stunning portraits of the native peoples who lived there.

To do this back then these early artist/documentarians had to literally carry a photography lab on their backs—or, rather, on the backs of their donkeys or in rickety photo wagons. The cameras they used were behemoths: huge view cameras with expanding bellows and heavy-as-lead lenses. With no such thing as high-speed film—much less digital—each plate for each individual image had to be prepared in the dark in a wet bath and then each wet-plate exposure had to be developed immediately.

|

|

| They look like photo artifacts from the Civil War era, yet they are contemporary tintypes done by John DiMartino, Jr. Top: abandoned herring smokehouse in Trescott, Maine. Bottom: restored fishing weir near the Pleasant Point Reservation of the Passamaquoddy Nation, near Eastport. (all tintypes © John DiMartino, Jr. All Rights Reserved.) |

Exposures often took multiple seconds—with no guarantee of sharpness or success.

But when it all worked, oh Lord, what gorgeous, ethereal, detail-laden photographs! These monochrome coffee-and-cream images made even the mundane magical.

|

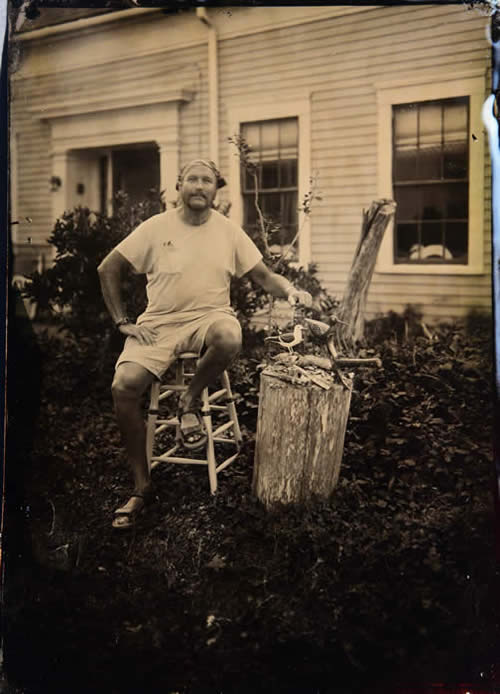

| Woodcarver, Eastport, Maine (John DiMartino, Jr.) |

Worth the effort? Ask John DiMartino, Jr., a spiritual and artistic heir of these past masters who works today making one-of-a-kind wet plate collodion tintype prints, identical to ones that saw huge popularity during the Civil War. I met John this summer after he had just finished a three-week artist-in-residency at The Tides Institute and Museum of Art in Eastport, Maine, and was about to begin a marathon of landscape and portrait shooting in nearby rural Lubec (the easternmost point in the United States, where my wife and partner Judith Goodman and I live and teach photography every summer.)

“You’ve got to talk to Frank,” several folks told him, knowing that I had written and photographed the 1998 book Down East Maine / A World Apart.

|

| Tintype Master John DiMartino, Jr., photographed with one of his several view cameras on a perfect evening in Lubec, Maine. (© Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved.) |

After just a few minutes talking to this animated fellow New Yorker, and looking at just a fraction of the images he already had made, it was clear that DiMartino was the real deal. It also was obvious that he would have looked right at home in the Old West with his photo ancestors. Their equipment would be virtually identical—only today, instead of donkeys hauling John’s vintage gear from one spot to the next, he now uses a honking big Toyota Tundra filled to bursting with equipment, chemistry and a portable wet plate darkroom as he shoots his tintypes Down East.

|

| Wet plates need to be developed immediately. Here, John develops one of his tintypes from the back of his photo truck. (Van Riper photo.) |

Sure, there are other photographers who love large format shooting—including making tintypes (more formally called ferrotypes.) But only a mere handful, John estimates, are as adamant (read: compulsive) about adhering to all the historic steps used to create these remarkable images.

On the pull of adhering to all aspects of this antique process, John notes: “I spent my entire career in front of a computer, but I’ve always loved the idea of making something with my own hands” For this reason John is one of only a handful of tintype photographers working today who does everything the way it was done more than a century and a half ago. For example, you can buy mass-produced aluminum plates that have been coated with black enamel that will then be treated with light-sensitive commercially-prepared collodion. But in virtually all cases, John insists on treating his tin plates one by one with a traditional black varnish that he makes himself. The process is called “Japanning,” and calls to mind the shiny black varnish on Japanese wooden furniture popular during the time of Commodore Matthew Perry, the American Naval officer who helped open Japan to the West in the 1850s.

And John does not stop at Japanning. He mixes his collodion solution himself from dry chemistry and uses precisely all the other chemicals that were used to make tintypes so long ago. (In watching John work this way, I could not help but compare him to a hardcore Civil War re-enactor.)

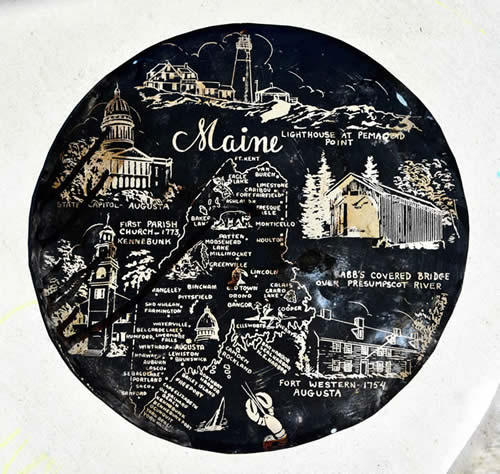

Tin is the operative word, in part because of its universality. John prides himself on occasionally making “hobo tintypes” from materials salvaged from such mundane things as old saltine and toffee tins—and, in a current project, the backs of antique round bar trays made of tin and featuring maps of all the states. (He has a whole set and plans to put an appropriate state scene on each.)

|

|

|

|

| 'Hobo' tintypes made on hand-prepared found objects. Top: Old smokehouse in Lubec done on an old tin bar tray--reverse side shows the Maine map. Bottom: Mulholland light near Campobello, NB, Canada done on a repurposed vintage toffee tin, showing Queen Elizabeth's parents. (John DiMartino, Jr.) |

In 2018, John’s expertise landed him a lengthy, arduous—but artistically rewarding--gig helping to produce a huge series of tintypes to promote the popular Paramount Television series “Yellowstone,” starring Kevin Costner.

John worked under Sarah Coulter, then senior photo editor for the Paramount Network and an accomplished tintype photographer herself. Coulter wanted to document cast and crew using the tintype process and she hired John to arrange the production line, including multiple stations to develop Coulter’s tintype prints on location (and on the fly) in Montana. Remember: this is wet plate photography, meaning that the plates cannot be allowed to dry. Usually, this means you have only 15 minutes from shooting an image to developing it as a metal print. John’s production line worked so well that Sarah was able to produce hundreds of gorgeous tintype images.

|

A bearded John is in foreground with photographer Sarah Coulter (hand to chin) along with the rest of the tintype production crew--on the set of 'Yellowstone' |

DiMartino, who turns 50 next year, is a solidly built civil engineer who spent 20 years with the Environmental Protection Agency in New York until he no longer could stomach the systematic “dismantling of environmental regulations” by the Trump administration.

With two decades at EPA under his belt, and after years of photography study and apprenticing--and after saving up for just such a move--he has granted himself a two-year sabbatical to pursue wet plate photography. During this time, John told me, he will try to build a portfolio of great images that could establish his reputation as a tintype master and lead to gallery and museum recognition (and also, I would hope, to a book.)

Based on what I have seen so far, I am sure he will succeed.

|

| This ain't no iPhone...John working in Trescott, Maine, photographing an abandoned smokehouse that is being restored by four friends of ours. (Van Riper photo.) |

During John’s summer tintype marathon in Maine, I recalled working on my own Maine book and recalled too the remarkable, exponential, power of networking. John was no slouch in contacting, not only me, but any number of other folks, all of whom recommended places and people for him to photograph.

Judy and I were able to guide John to a stunning abandoned herring smokehouse in nearby Trescott, that is being restored by four friends of ours and we spent the better part of one day with John as he manhandled one of his big antique view cameras to various vantage points. At each site he would make a series of exposures, then race back to his truck to develop his prints and see what he got.

The images John got were wonderful, but, truth to tell, I’m not about to give up my digital Nikon or my film-loving Leica M6.

I’m sure my knees and back will be grateful.

---------

Frank Van Riper Fall photography class at Glen Echo Photoworks, Glen Echo, Md.

REGISTRATION: ‘La Faccia’:

https://reg126.imperisoft.com/glenechopark/ProgramDetail/3434383636/Registration.aspx

ALSO…

REGISTRATION: ‘Photographing Artwork’:

https://reg126.imperisoft.com/glenechopark/ProgramDetail/3434383637/Registration.aspx

REGISTRATION: ‘Glen Echo Night Photography’:

Section one, October 20th—

https://reg126.imperisoft.com/glenechopark/ProgramDetail/3434383830/Registration.aspx

Section two, November 9th—

https://reg126.imperisoft.com/glenechopark/ProgramDetail/3434383832/Registration.aspx

-0-0-0-0-0-

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, Lubec, Maine

Join us for another magical summer NEXT year--2022

Master Photo Classes with Frank Van Riper

These intense, three and a half-day, limited enrollment classes are aimed at the more advanced student, who already has taken a photo workshop and who is familiar with basic flash. Maximum enrollment of just five. NB: previous Master Classes were fully booked almost immediately.

2022 Master Photo Class dates:TO BE ANNOUNCED

Come photograph in one of the most beautiful spots on earth.

-----------

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 10/6/21]

|