My Best Floral Photograph--so far

How Penn, Steichen and a friend finally converted me

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

|

| 'Parrot Tulips / 2022' ©Frank Van Riper |

For years (hell decades) I did not make closeup photos of flowers. If I were to be the judge at a local camera club competition, members came to know that they should not submit flower pictures that evening since I tended to hate them—and said so.

Why?

Because virtually all of the flower pix I had to judge back then were the same—available sunlight macro images of one flower—most often dead center in the frame—with perhaps a pollinating bee for visual interest.

These color images not only were boring; they showed absolutely no influence of, or input by, the photographer. The flower was doing all the work. All the photographer did was push the button in bright sunlight.

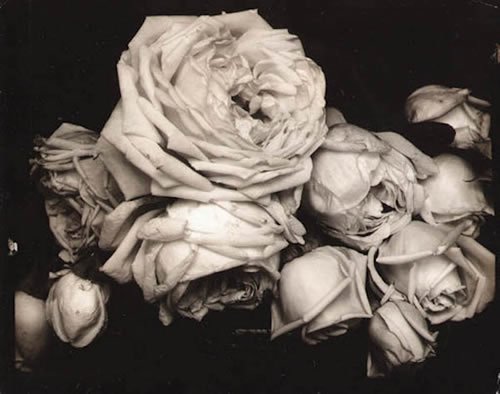

In fairness, I also had been spoiled by masters who came before me, most notably Edward Steichen (1879-1973 ) and Irving Penn (1917-2009.) Their portraits of flowers—as portraits they surely were--convinced me (until now) that I never could do any better than they in depicting what are among nature’s most colorful, sensuous, creations. For example: take Steichen’s glorious black and white photograph “Heavy Roses,” made in France in 1914, just before the beginning of the First World War. It shows abundant roses slowly withering—“a metaphor for the ensuing tragedy” of a World War, noted one critic.

|

Edward Steichen's lush 1914 image "Heavy Roses" was made in France just before the outbreak of World War One and to some seemed a harbinger of global calamity. |

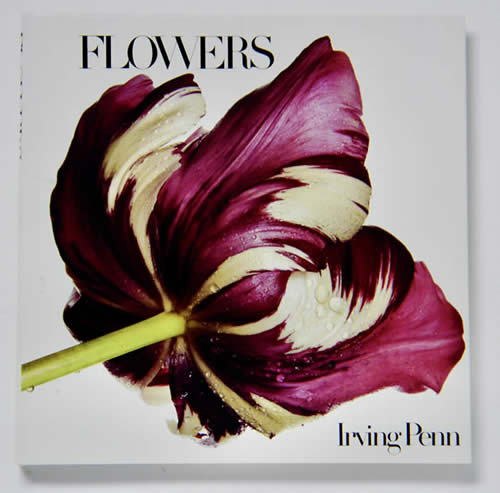

And decades later, Penn--a true Renaissance man of photography (eloquent in portraiture, still life, advertising, fashion, etc.) set the bar even higher with his own depictions of flowers, parrot tulips especially. Shot for the annual Christmas issues of Vogue magazine, Penn worked from 1967-73 to produce studio-lit closeups of everything from tulips to peonies, all beautifully rendered.

|

| One of the best floral photographs ever: Irving Penn's openly sensuous rendition of a brightly colored parrot tuip--a tightly controlled studio portrait. |

Just look at the parrot tulip on the cover of his book Flowers—shot from a totally bizarre angle (from the stem looking up) and marvel how from this angle he has captured the flower’s wide-hipped voluptuousness. No direct sunlight here: this shot was made in the studio against a white background at a very small aperture to show everything in sharp focus. As always, Penn was in total control of the image—down to the dew (or are they artfully applied water droplets—or even glycerine?) on the outside petals.

No wonder I was intimidated.

It’s not that I never shot photos of flowers—every so often I’d make one that I considered a keeper. One such image (of parrot tulips, in fact) came years ago when Judy and I were shooting weddings, often working with Suzann Stotlemyer, for our money the best, most creative, florist in the DC area. Knowing my wife’s love of flowers (Judy’s also a master gardener) Suzann often would drop off leftover flowers on our porch after a job. One morning, we woke up to a bunch of brightly multi-colored parrot tulips.

Having used my studio lights on flowers years earlier to disappointing results, I was taken by how a group of these parrots, placed in a vase in our living room, shone in the raking light from a nearby set of windows. Composing carefully to show off two aspects of the petals from two different flowers---as well as a lovely pod near the center, I made an available light shot, and loved it.

But that was then. Except for a few workshop images that I made while teaching my photo Master Classes in Maine—usually of ferns, etc.—I never really shot any more floral closeups.

|

| Good to have a friend who's a florist. Suzann's gift of these parrot tulips many years ago after we worked a wedding together produced this riotously colorful image. © Frank Van Riper |

|

| This image of a fern, made as I taught one of my photo Master Classes in Lubec, Maine, pretty much defined my floral/nature photography. (I call it 'The Creation,' borrowing shamelessly from Michelangelo.) © Frank Van Riper |

Until now.

Looking back, I suspect the inspiration actually started in Maine over this past summer when I made what I thought was a very successful series of pictures of my favorite drinks—from wine to Scotch to beer—all under dramatic lighting, either natural or with flash.

Then a month ago, after Judy and I had returned to DC, Erica came to dinner bearing tulips.

Our dear friend, who also is an excellent photographer, usually brings wine, but Erica said she could not resist the lovely, nearly monochromatic, parrot tulips she saw that afternoon at the market. Judy immediately put them in a vase, augmented by some small toad lilies from her own garden, and we all sat down at the dining room table for another simpatico dinner, but not before I announced, “I’ve got to photograph these tulips in black and white.”

I waited a few days for the parrots to open up a bit, then set about to make good on my promise. Because the flowers were virtually monochrome—all pale greens and white—I knew I would work in BxW. But I also wanted to render the flowers as if lit by a theatrical spotlight, with one flower highlighted while the rest remained in subtle, yet still detail-rich, shadow.

I found myself relying on techniques I teach in my portraiture class ‘La Faccia’ [The Face], using in this case a small portable Vivitar 285 strobe unit on a tabletop light stand positioned to the left of the flowers and pointing downward. To create a spotlight effect, I used painter’s tape to attach a simple toilet paper tube to the flash head to act as a light-directing snoot. (I also taped over the rest of the flash head, to direct light only through the tube’s narrow hole.)

|

| A simple set-up makes for simple, elegant light. © Frank Van Riper |

The gorgeous flowers themselves presented a compositional challenge that wound up with less being more, especially since I wanted to isolate only one stunning flower against a midnight black background. (In fact, the background cloth was dark blue (see below): a small manageable piece of blue felt--not my regular black backdrop that is huge. Since I was working in BxW, the background color didn’t matter as long as it was dark. Note, too: when using flash, I prefer to use felt backdrops versus seamless paper since paper sometimes can show errant reflections from your lighting, especially if you are working in closer quarters.)

|

| A real 'before' picture, this view shows how ordinary everything looked before I used a number of studio lighting techniques. |

With the composition set and the lighting in place, all that remained was making sure the lighting and the exposure gave me what I wanted: dramatic highlights and detail-rich shadows. Arranging my light to barely kiss the forward tulip created a strong yet subtle main light on the front flower, while diffuse light bouncing up from the dining room table helped render detail on the floral elements behind. I shot at ISO 250, f.16 at 1/125th of a second.

The final image frankly thrilled me—especially when I had gorgeous big giclees made on heavy stock by Old Town Editions of Alexandria, Va.

I look forward to continuing this BxW series of unusual flowers ready for their close up. Next up, perhaps: Calla lilies.

-------

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys, Lubec, Maine

Join us for another magical summer in Down East Maine in 2023...

Master Photo Classes with Frank Van Riper

I have taught in several different places—from Washington DC to Umbria—but my Photo Master Classes in Lubec, Maine may be my favorites for their small size (five students max) and their remarkable setting—arguably the most beautiful coastline in the United States. (Sorry, route 1 in California.)

These intense, three and a half-day, limited enrollment classes are aimed at the more advanced student, who already has taken a photo workshop and who is familiar with basic flash. Maximum enrollment of just five. Open to vaccinated students ONLY. Enrollment through the famed SummerKeys Music and Arts workshops in Lubec, Maine--the easternmost point in the United States. First class will be July 17th-19th, 2023; second will be August 7th-9th. NB: previous Master Classes were booked almost immediately.

More Information: GVR@GVRphoto.com

To enroll: www.SummerKeys.com

Come photograph in one of the most beautiful spots on earth.

-----------

Van Riper Named to Communications Hall of Fame

|

| Frank Van Riper addresses CCNY Communications Alumni at National Arts Club in Manhattan after induction into Communications Alumni Hall of Fame, May 2011. (c) Judith Goodman |

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 1/5/23]

|