Go Back to current column

Frank Van Riper Winter classes at Glen Echo Park,

SUMMER Photo Workshops, Lubec, Maine (below)

Made by Hand--and Heart

Or why an iPod will never rival a Leica, or a Steinway

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

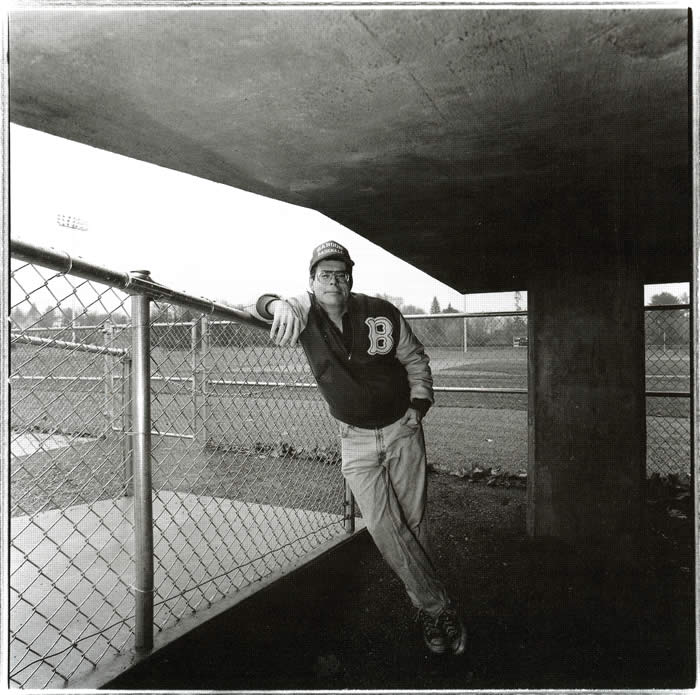

Years ago, in a conversation with Stephen King, the bestselling author talked about the craft of writing and what made it special.

“That’s one thing about writing,” said King, on a miserable drizzly November morning in Maine after I had shot his portrait outdoors, “it doesn’t change from century to century. It’s still hand work.”

Hand work—the image sticks because it is so apt. Like a mason laying bricks, a writer puts one word alongside the other, hoping to make a solid structure. The mason does it one brick at a time; the writer does it one word at a time. There simply is no other way.

Hand work—the kind that always leaves a unique human imprint, no matter how simple, how intricate, how often done.

|

|

|

| Mega-author Stephen King photographed at the senior little league field in Bangor, Maine, that he and his wife Tabitha built for the city. The craft of writing he said, was, is and always will be 'hand work.' (c) Frank Van Riper |

|

|

When I was a political reporter I did a Sunday magazine piece on political memorabilia following Jimmy Carter’s election as president in 1976. Talking with the director of the Smithsonian’s division of political history, I showed him a few of my favorite political buttons and asked what kind of artifact he coveted most from, say, the Democratic National Convention that had nominated Carter for president that previous summer in New York City.

No question, the official responded. Rather than any mass-produced button or poster, he said he went after a handmade banner that actually had hung from the railings in Madison Square Garden during the convention.

Again: one of a kind, made by hand, and in this case actually used during an historic event.

To be sure, something made by hand can be rustic or elegant—a three-legged milking stool cobbled together by a farmer centuries ago, or a Steinway grand piano made this year and consisting of some 12,000 parts, each (amazingly) still made and assembled by hand into a musical work of art.

In an electronic and digital age dominated by robotics, computer generation and automated mass production, there still is a revered place for something one-of-a-kind, something made by hand

In photography I believe that applies not only to cameras but also to photographic prints.

In photography one might think first of hand-made cameras--lovingly made wooden view cameras, for example--but perhaps the best example (if not the only example today) is the Leica MP 35mm rangefinder camera, an exquisite piece of all-manual engineering that lives up to Leica’s boast that the “MP” stands for “mechanical perfection.”

|

| The glorious Leica MP 35mm rangefinder camera. They do not get any better, or better made, than this--and they are made by hand, to the tune of more than four grand apiece for the body. To serious photographers--and, unfortunately, also to some dilettantes--it's worth it. |

I reviewed this camera when it first came out seven years ago and, even as a longtime Leica user, I was floored by the heft, ruggedness and glorious precision of this “instrument.” Note: list price on an MP body today is more than $4,000. Interestingly, in 2006 Zeiss introduced a rangefinder camera that obviously was geared to compete with the pricey Leica—the body was infinitely cheaper and it took Leica lenses. Though I was impressed by the (also cheaper) Zeiss lenses, I could not get past how chintzy and flimsy the camera body felt compared to the Leica.

Granted, here is where some folks will claim that the only reason Leicas can be sold at all today is that dilettantes who need to have the very best (read: most expensive) cameras regardless of whether they can use them well will keep outfits like Leica afloat (and presumably carmakers like Ferrari and watchmakers like Rolex.) This is what I call the surgeon and pilot theory. Though I do not mean to knock either profession, I have run into or heard about enough highly paid medical and airline professionals who are photography buffs to know that more than a few of them latch on to the next new thing almost as fast a Tiger Woods used to latch on to new girlfriends.

And they do it because they can afford to do it, not because it improves their photography worth a damn.

That having been said, there are far more of us who not only value fine craftsmanship, but also have come to expect fine craftsmanship to translate into dependability when we are working—sometimes in difficult, distant or inhospitable locales--with only one chance to make a shot.

Case in point, while working on our new book, Serenissima: Venice in Winter, my wife Judy's electronic Nikon N90 fell from her lap to the floor of a vaporetto as she rose to leave the water bus.

It was fried.

That same trip I somehow dropped my all-manual Leica M6 as I was walking along the street. After my life passed before me, I picked it up and couldn’t even find any sign of where it hit. The camera itself was (and remains) fine. Years later, on closer inspection, I saw that one of the fastening holes for my shoulder strap was misshapen: obviously the point of impact. Inside, however, the camera was perfect.

That’s what you pay for.

But workmanship and dependability aside, there also is the appeal, I believe, of the human presence, not only in equipment, but on the work it produces..

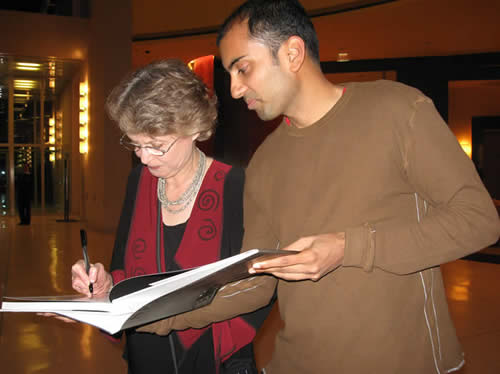

Why, after all, will someone stand in line waiting for an author to sign—or better, to sign and inscribe—his or her book? Answer: to make the volume, valuable to the buyer already for its content, even more so for the ineffable, singular, human imprint of the author.

|

| Judith Goodman, my wife, professional partner and co-author, signs copy of our new book, Serenissima: Venice in Winter, for photographer Praveen Mantena during a reception, exhibition and book-signing at the Italian embassy in 2008. |

What makes an original painting or drawing more valuable than even the most painstaking digital reproduction? Answer: even if the reproduction is signed it remains a mass produced, often computer-generated, clone. The original work of art is one-of-a-kind, and the artist’s pencil or brushstrokes, best seen only on the original, offer a unique vision of the human hand at work.

With photography, I have written before of the market appeal of individually signed wet darkroom prints, especially those made one at a time by the photographer him or herself.

I take nothing away from my colleagues who work totally digitally, and who, after painstakingly selecting enough curves and levels, and sliding enough sliders to tweak an image to perfection in PhotoShop, create a gorgeous photo with a final push of a button.

The beauty of this process is that, once the photographer has created his or her master print, it can be re-generated ad infinitum—again with the push of a button.

The curse (and blessing) for troglodytes like me who still use film and who work in the black and white darkroom is that each time we make a print (even using the same procedures and darkroom notes we have used for years) the print itself is and always will be one-of-a-kind by dint of the simple fact that the photographer—not the Epson—is making each print, imparting something of him or herself in every one.

Hand work.

Working by hand, and by heart.

Or put another way: why an iPod will never rival a Leica or a Steinway.

Frank Van Riper Winter classes,

field trips, Glen Echo Park, Md.

Great Portraits with Simple Lighting ($275)

Thursday, January 21-February 11, 7-10:30pm

Achieve studio-quality results with equipment as simple as a flashlight, aluminum foil and a toilet paper tube. A great way to learn the basics and have fun doing it.

National Gallery, East Wing, Field Trip ($150)

Sunday, January 17

Spend the day photographing in one of Washington's great spaces, where opportunities for landscape, abstract and portrait photography abound. There will be an orientation session about a week before, followed by a potluck dinner and critique at Frank's home after the field trip.

For information contact: GVR@GVRphoto.com or go to www.glenechopark.org

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys

Spend a week of hands-on learning and location photography with award-winning husband and wife photographer-authors Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman. Working from their stunning home in west Lubec overlooking Morrison Cove, (see photo above) Frank and Judy will cover basics of portraiture, landscape and documentary photography during morning instruction, followed by assignments in multiple locations including Quoddy Head State Park, Campobello Island, NB and the colorful town of Lubec itself. Daily critiques and one-on-one instruction. NO entrance requirement. Minimum age for attendance is 16. Maximum number of students each week is six . Students supply their own digital camera.

Read more about the Workshops in Frank’s column:

http://talkingphotography.com/archive/2009/photowork.htm

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. His photography books include Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart, and Talking Photography, a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over ten years. His latest book (done in collaboration with his wife and partner Judith Goodman) is Serenissima: Venice in Winter www.veniceinwinter.com

Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 1/10]

|