Go Back to current column

Join us in Umbria, Italy, in October!! (see below)

Losing the Decisive Moment

...why newspapers matter in the digital age

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

These are strange times to be a photographer.

Never has so much photography been seen by so many, especially on the internet. From politics to portraiture, from sports to documentary, from news to culture.

Both still and video.

(Oh, and did I mention online pornography? Except for the occasional dirty cartoon, it is still, after all, photography.)

In all its forms photography has never been so widely disseminated.

And yet never have photographers themselves been so widely devalued.

|

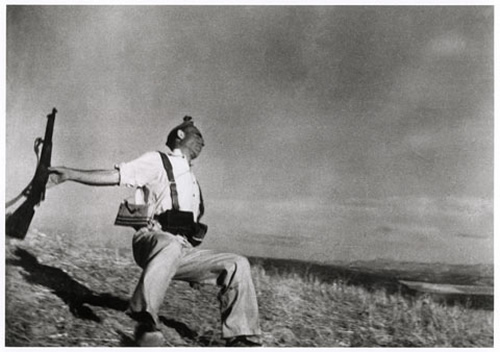

The Decisive Moment defined: Robert Capa's famed image from the Spanish Civil War, commonly called "Death of a Loyalist Soldier." The photo, actually called "Loyalist militiaman at the moment of death, Cerro Muriano, September 5, 1936," is widely regarded as the greatest war photo of all time. Charges that the shot had been staged have been thoroughly refuted by Capa biographer Richard Whelan. (Lo-res fair use image from Amherst College Magazine.)

|

Any number of factors have contributed to this, and these are some of the most important, in my view:

--The exponential improvement of digital technology, in both image-making and printing.

-- The aforementioned explosion of the internet

-- The effective demise of newspapers and magazines

-- The willingness of professional photographers, who should know better, to sell their work for next to nothing.

Though the deleterious effects of these factors can be seen almost everywhere, I fear the most dangerous outcome of undervaluing the work of the individual professional photographer will be in the coverage of news. It costs money to cover news right, and news organizations today have precious little money to spend. Cutbacks in serious (note: I said serious) news coverage can be as dangerous to the health of the body politic as failure to pass a comprehensive health care plan can be to our own collective well-being (And look how close we came to booting that one.)

We are, I fear, in danger of losing far too many Decisive Moments in the form of hard news coverage; coverage that, in turn, helps inform and guide us through the messy business of democracy. In other words, real news coverage, not the truculent in-studio blather of a Beck or a Palin or a Limbaugh.

Nowadays, everyone is a photographer—or at least thinks he is. And often, I have to admit, that person has good reason to think so. Where once any photographer worthy of the name would have to know how to load a Hasselblad or a Leica without blinking, or operate a view camera, or light a portrait, now anyone with even an adequate digital point and shoot set to Program and a high enough ISO can make an acceptable photograph.

Not a great photograph, mind you, or even a good one—but acceptable. If age 60 is supposedly the new 40, then acceptable has become the new good in too many aspects of photography today.

You see it all over: mediocre headshots on business websites and advertising, godawful travel photos on YouTube, suspiciously generic images in advertising and web design, less than stellar news images, especially from unvetted stringers working in war zones where once staff shooters would be sent.

In the case of the lousy headshots, the seductive ease of digital has prompted some firms--thinking “hey, even my brother-in-law could do this”--to use individual snapshots or, worse, photos of people stuck up against a wall in the office. This, mind you, is the business’ public face to the world.

The YouTube phenomenon is not really new—think of the old days and of sleeping through someone’s slide show of vacation snaps—it’s just more ubiquitous. For example, I put up a professionally done video of Judy’s and my work on our gorgeous book Serenissima: Venice in Winter and I am delighted that people can access it so widely. But when they go to “Venice Photos,” or something similar, they also have to wade through (I’m sorry) a cavalcade of really dreadful travel snaps of Venice before they get to ours, as well as the work of other real photographers.

|

Judith Goodman had to wait for precisely the right moment to make this beautiful image illustrating acqua alta in Venice's Piazza San Marco. (c) Judith Goodman, from 'Serenissima: Venice in Winter.'

|

Bland illustrations in magazines, etc? Anyone in the visual or picture industry, can tell you how the ostensible democratization of digital has decimated the stock market.

Not Wall Street, but the market for first rate stock photography. Where once serious stock shooters were able to make real money shooting on assignment and on spec for clients around the world, now, in some cases through their own actions, they are getting only pennies on the dollars they used to earn with their images. Why? The siren song of unloading their stock files en masse in royalty-free deals that were supposed to make it all up on volume. Add to that the Midwestern housewife profiled recently in the New York Times and you can understand how inevitably this market has changed.

[The woman—a very good amateur digital shooter—is delighted that folks are paying her for the generic images of family, etc., that she sends to her agency, earning her a respectable and necessary freelance income. And because she does not have to sort and file thousands of film slides—just edit her digital take and upload selects—she has no problem making less than a fulltime pro shooter might have to earn to stay afloat.]

There is a vicious cycle at work here, beginning with the simultaneous development of the Internet and digital photography.

The internet—giving one the ability to cruise the world from one’s computer—may literally be the greatest technological advance since the telephone (not surprisingly, another way for folks to communicate and gather information.)

|

|

Two decisive moments in very different settings: Beautiful top shot of local bullfight in Mexico combines key action between matador and bull with a near-abstract pattern of pennants. (c) Daniel Taylor. In my 40-plus-year-old image 'Penn Station Farewell' (bottom) I waited for just the right moment as the two women communicated through the train window. (c) Frank Van Riper

|

For reasons that still remain a mystery to me, management at newspapers all over the country and around the world viewed this great new phenomenon as merely a gimmick that would lead readers TO their printed product, and not AWAY from it in droves as has proven to be the case. So what did the geniuses in the blue suits do a decade or so ago when the internet was young? They decided to GIVE AWAY the online version of their newspapers, as if it were a loss leader. [These folks also hoped that once people grew accustomed to the internet version, they would flock to buy advertising on it.]

The result, however, was diminishing paid readership--as people quite logically dropped their newspaper subscriptions and scooped up the freebie online version--and a consequent loss of display and classified ad revenue as businesses and individuals used everything from Craig’s list to eBay to you name it to hawk their goods to the burgeoning internet market.

Oh sure, many people (of a certain age, I suspect) still get a paper paper—and I am one of them. We subscribe to the daily Washington Post. But recently, as I trundled out one morning to pick up the paper in its little plastic condom, I was struck by how insubstantial it felt. For a minute I thought it was the local shopper that we also get. But no, it was the once-thick Washington Post suffering from advertising anorexia.

As years went by, and some publishers realized that their classified and display ad holes were shrinking faster than a wool suit in a hot water wash, some outfits like the New York Times tried to make money from their online versions by charging for prime content. “TimesSelect” was the grey lady’s shortlived attempt to get online readers to pay for its top columnists and other features. (And I, as an ex-newspaper reporter, happily forked out what would have been about 100 bucks a year for this privilege.)

But the genie already was out of the bottle. No one, or at least no one in sufficient numbers to matter, was going to pay for something that once had been free. TimesSelect died.

And with it, I fear, may be the future of print journalism, written and photographed, unless a way can be found to stop the hemorrhaging. The loss of ad money not only shrinks a paper’s budget, it also shrink’s a paper’s “news hole”—the space for stories and pictures. Less money for stories and pictures means layoffs for reporters, editors and photographers. And these layoffs, in turn, mean that stories will not be covered, important events will not be photographed, not just for tomorrow’s paper, but for history.

Three people on a bench can be just a snapshot, but at the right moment it becomes a photograph. Here, Nick Strocchia's image, 'Meetup/London' captures a tender, universal pose. (c) Nick Strocchia

Ah, respond some, maybe it’s about time the “lamestream press,” as Palin likes to call it, got its comeuppance. Let real-people “citizen journalists” tell it like it is.

Decades ago, the press critic and essayist A.J. Liebling had this to say about a preponderence of independent newspapers:

“Different reporters see different things, or the same things differently, and the reader is entitled to a diversity of reports…a one-man account of a crisis is like a Gallup Poll with one straw….”

I think that in terms of an individual gathering one’s news by oneself on the internet, the overwhelming tendency is for anyone—even the most objective or fair-minded person—to fall victim to the echo chamber effect of gathering the views of only those with whom one agrees. To present "a diversity of reports" is porecisely why the conservative Charles Krauthammer shares the Washington Post’s opinion page with the liberal Colbert I. King; why David Brooks and Gail Collins share space in the New York Times.

As for the “citizen journalist” I find the term almost an oxymoron and stupid in the extreme. Never mind that the “citizen journalist” presumably is too busy going to his or her regular job to actually cover anything--at least on a regular basis--or consider issues in depth by doing real research, real interviews, all of which take real time.

Does anyone go to a “citizen doctor” or to a “citizen lawyer” when the going really gets tough? The view that somehow, without any real training in objective or at least impartial news reporting, “real people” in non-journalism jobs have the innate ability to produce a balanced, complete, nuanced, straight-from the shoulder take on the news from their self-generated blogs or websites is—I’m sorry—fatuous bullshit.

Better for the future of our admittedly messy democracy to find a way for independent newspapers to flourish once again. One current thought is to charge “micro-payments” every time a person goes to a paper’s website. This is an idea touted in some form by Rupert Murdoch, the rightwing Australian media baron, who happens to own The New York Post. Along with the Times, the NY Post was my biggest rival when I was a reporter and later an editor in the Washington Bureau of the New York Daily News nearly 25 years ago. I hated what Murdoch did to the NY Post, but at least he kept it afloat.

In his current endeavor I wish him only success.

The Umbria Photo Workshop

The trip of a lifetime, Oct. 16-23, 2010

Frank Van Riper Join internationally acclaimed husband and wife photographers Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman for a weeklong photographic workshop under glorious fall skies in one of Italy’s most beautiful regions.

Frank and Judy, authors of the award-winning book Serenissima: Venice in Winter, will share their image-making techniques with a small group during a week covering everything from landscape photography in the verdant hills of Umbria to location portraiture in its closely held truffle fields.

Participants will travel by guided excursion to several of Umbria’s storied hill towns, including Perugia and Assisi, and receive individual attention during daily critiques.

Package includes 6 nights in the fully restored 17th century villa Fattoria Del Gelso in Cannara, located on a 40-hectare working farm literally walking distance from colorful shops and restaurants and centrally located in the shadow of Assisi

This is a trip designed for relaxed learning and sightseeing via foot, bicycle and van, taught by two experienced location photographers whose work has been exhibited in and acquired by major museums in the United States. Frank and Judy are molto simpatico teachers who will turn your photographic vacation into a once-in-a-lifetime adventure.

October 16-23, 2010

Price per person: €1500 (convert to dollars)

Limited to 6 participants

Package includes:

--6 nights in the private villa Fattoria del Gelso

--welcome and farewell dinner

--all breakfasts

--vineyard tour and private lunch

--daily happy hour

--individual critique and instruction

--private guided walking tours

--pizza-making party at the villa

--ground transportation throughout your stay

—FURTHER INFORMATION: www.experienceumbria.com

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. His photography books include Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart, and Talking Photography, a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over ten years. His latest book (done in collaboration with his wife and partner Judith Goodman) is Serenissima: Venice in Winter www.veniceinwinter.com

Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 6/10]

|