Go Back to current column

Lubec Photo Workshops – Summer, 2011 (see below)

The Ability to Repeat

Achieving excellence when you are not a genius

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

“The first leg of the College’s anti-tuition drive was a little lame, but it probably bore enough fruit to be considered more than worthwhile."

I am embarrassed to claim authorship of that discordant sentence, with its mixed metaphor and clanging construction. I wrote it in the 1960s in New York City when I was a young student reporter for The Campus, “undergraduate newspaper of the City College since 1907.”

Happily, the sentence never saw print. My father, who besides being a bank’s note teller was an unpublished author and a hell of a writer, smilingly pointed out that legs, lame or otherwise, tended not to bear fruit. I subsequently changed the draft of my article to say that the first leg of CCNY’s campaign to maintain free tuition at the venerable institution “bore its weight well enough” to be a qualified success.

This episode, obviously not a high point in my career as a writer, nevertheless was formative since it helped me learn from my mistake—or at least be more careful with metaphors. I thought back to this recently after reading separate articles about performers of genius: one a “prodigiously gifted” musician, the other the best closer in baseball.

Esperanza Spalding, a virtuoso bassist, singer and composer, displayed her genius when she was four years old, said a profile in The New Yorker. When Spalding was four, “she heard her (mother) struggling with a simple piece by Beethoven. Afterward Spalding climbed onto the bench and played the piece by ear.”

|

| Young and beautiful, Esperanza Spalding also is a genius, who demonstrated her talent at a very early age. |

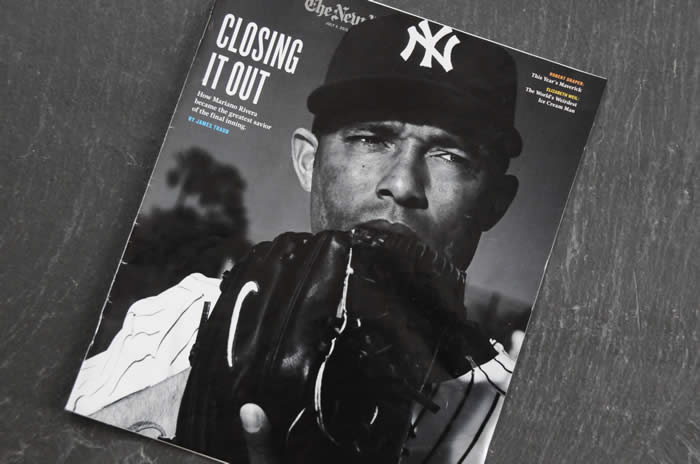

In the case of New York Yankees pitcher Mariano Rivera, he noted simply that his amazing ability to preserve a late inning lead—and thereby a win for his team—with icy nerves and a cut fastball “is a blessing from the Lord.”

“When he gives you something it’s yours,” Rivera was quoted as telling the New York Times Magazine. The reporter writing the piece interpreted this to mean that Rivera’s gift could not be shared regardless of how generous he might be in teaching young pitchers or in coaching his contemporaries. You either have it or you don’t.

If one assumes that the vast majority of us are not performers of genius like Spalding or Rivera, then where does that leave us when we write a story, play sports, sing a song, take up an instrument, act onstage—or make a picture?

Not all that far from the geniuses, I submit, if we are willing to put in the time. [And in fairness to Spalding and Rivera, none of what they accomplished could have happened without years of work and practice.]

Malcolm Gladwell, the dynamic young New Yorker writer and author, has sold thousands of books noting social trends such as The Tipping Point. One of his more recent works, on what makes people successful, mentions the theory of 10,000 hours. Gladwell maintains that a person can rightfully view him or herself as an expert—or perhaps more importantly, be viewed by others as an expert—once he or she pursues something, and does it, for at least 10,000 hours.

Note: the author does not say study something for 10,000 hours or think really hard about it for 10,000 hours. It is the physical act of doing something over and over for a long period of time that confers expertise. In this I am reminded of a friend of mine in high school who hoped to become, but never succeeded in being, a famous photographer.

“I’m an artist because I think great thoughts,” Marty once told me. But even then I thought this sounded fishy. Being an artist also meant doing something, right?

Or perhaps more correctly: being an artist meant doing something right.

And not just right, but right nearly every time.. “The ability to repeat is both mental and mechanical,” Boston Red Sox catcher Jason Varitek said of Mariano Rivera’s amazing pitching consistency, a product both of talent and of training. Flutist Eve Friedman (who with her husband, pianist/composer Roberto Pace, comprise the Philadelphia-based Halcyon Duo) put it to me this way: “A student practices till he gets it right; a professional practices until he can’t get it wrong.”

|

| The fickle gift of genius. Mariano Rivera works as hard as any pro athlete, but insists his being the best closer in baseball is gift from God. |

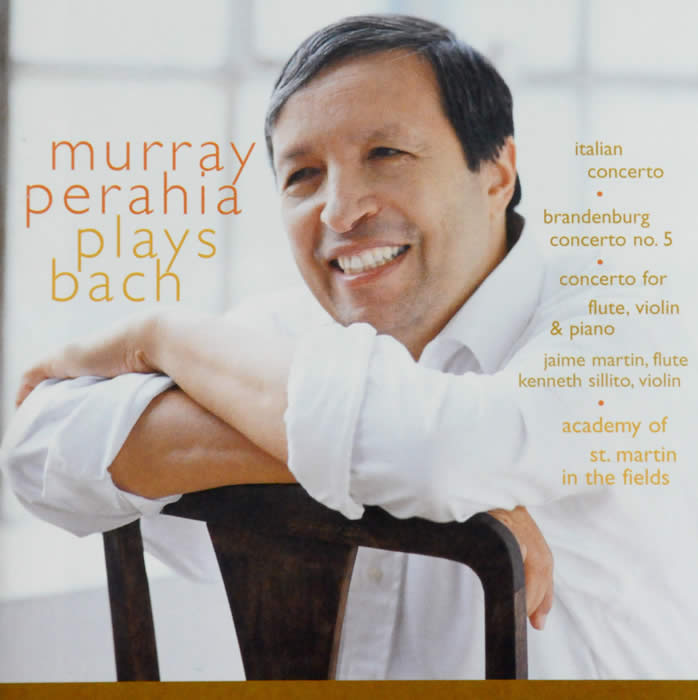

The ability, and more, the willingness, to do the work is what sets apart artists, musicians, athletes--doers of all kinds--from the rest of the planet. More than fifty years ago, for example, I briefly went to the same music school as Murray Perahia, who went on to become one of the greatest classical pianists of our time. Murray and I went to PS 90 in the Bronx; the music school was just off Fordham Road. He used to play at our school assemblies: a skinny little guy in a white shirt and red tie who played piano like a dream.

Walking to music class one afternoon after school I asked Murray his secret.

“You really do have to practice,” he told me almost apologetically.

It’s not rocket science. It’s all about putting in the hours. Most people can’t or won’t. I, for example, had better things to do than to learn the damned accordion. But what I think most people miss is how little effort it takes to make the leap from drudgery to pleasure. [It’s the leap from pleasure to mastery that takes up the bulk of the 10,000 hours.]

Remember the scene in “Julie and Julia” in which Stanley Tucci, playing Paul Child, a State Department information officer in post-World War 2 Paris, comes home to see his wife Julia (the astounding Meryl Streep) weeping as she chops a small mountain of onions with near-manic gusto? Julia Child was perfecting her technique for the stuffed shirts at Le Cordon Bleu, the famed cooking school where she just had enrolled and where the head mistress, at least, assumed she would fail. This was the drudgery that eventually turned into pleasure, and that helped turn a nervous American woman into an internationally renowned chef—and ultimately gave generations of grateful cooks, including me, Mastering the Art of French Cooking.

Reading Julia Child’s book, I am struck by its detail: about cutting a chicken, about different kinds of butter, about food chemistry. To be sure, Julia and her collaborators rhapsodized about the exquisite flavors and textures of food done well, but the key end-product—a collection of recipes offering precise measurements and repeatable results—could not have happened without a virtual 10,000 hours of experimentation.

Too often today technology robs people of the drudgery/pleasure of experimentation and of learning from one’s mistakes to achieve even a modicum of mastery. Everything, so it seems, is about shortcuts; doing it on the cheap. There are computer programs to help you write novels or screen plays (to jump-start your rise to big bucks from Hollywood.) There are CDs to help you learn foreign languages almost in your sleep. There are freeze-dried bags of ingredients to help you prepare gourmet meals in minutes to astound family and friends.

And, of course, there are cameras that do all of your thinking for you and tools like Photoshop to clean up after you when you have made a succession of piss-poor pictures.

I know I am not the only photography teacher who insists that workshop students make their photos only in manual mode, the better to think about light and how it affects an image. What better way to imprint on one’s synapses the right path to good exposure than to make bad pictures, then correct them incrementally, and learn from one’s mistakes along the way? (And, it must be said, how much quicker and easier it is to demonstrate this when working digitally.)

Add to this discipline a chance to move out of one’s comfort zone (close-ups of flowers, for example?) and try new things, the more the better, during an intense week of teaching, and you have a pretty good formula for improving your craft.

Even after a week’s workshop—or a class that meets once a week over five or six weeks—I have seen students discover the wide-eyed pleasure of mastering simple techniques that will improve their photography forever. In turn, they will make the slow, but inevitable, rise from to drudgery to pleasure; from “Dammit, why didn’t Program work this time?” to “Man, look at that!”

And this transition will make it much easier for them to keep at it—to practice, as Murray might say.

|

| It still knocks me out that Murray Perahia and I went to the same music school in the Bronx. Only he practiced. |

Often this step up is all that most people need to get real satisfaction out of their work, and for many this is as far as they will go in pursuit of excellence. After all, if I can pick out a few show tunes on the piano during a cocktail party (which, by the way, I cannot) maybe that’s all I ever hoped to do—or needed to do. I do not need to make Murray Perahia look nervously over his shoulder.

The rub of course is when, after an impressive recital of several songs, someone comes up to the piano and asks what else I can play. The honest answer would be: “nothing.”

This is one case where I believe photography has the upper hand.

It’s reasonable to assume that a photographer who has put in his or her 10,000 hours will have a far higher percentage of keeper images over a given period of time than will someone shooting over the same period—perhaps even under the same circumstances--who has not invested as much time in perfecting his or her craft.

Thus 10,000-hour Jane will produce far more first rate images than will 500-hour John during, say, the same photo safari to the Galapagos. But the important thing is that each photographer will have produced keepers, the result of their serious pursuit of photography, albeit at a different intensity.

If John is happy—even ecstatic—over his handful of keepers, perhaps remembering a time when his hyper-automated camera always seemed to be working against him, who is to say his joy is any less than that of the professional or semi-professional who hits the artistic bulls-eye far more often?

Or put another way: whenever Mariano Rivera comes into a game to protect a lead in the late innings, everyone expects him to be brilliant—and he had better be.

But in photography, the only person you have to please is yourself, and the only images you have to show are the ones you love. What percentage they represent of your total output is nobody’s business but yours.

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys – Summer, 2011

Next summer, Judy and I will once again be teaching three hands-on photography workshops in Lubec Maine, sponsored by the SummerKeys Music school. (www.summerkeys.com)

Our dates for summer 2011will be as follows:

July 11th through 15th

July 25th through 29th

August 8th through 12th

Classes are limited to only six participants each week. Each class includes personal instruction, ongoing portfolio review and a wide range of location photography, including portraiture, landscape and night shooting. Each week’s class ends with a slide show of students’ best work that is open to the public.

Since their inception in 2009, Judy and I have tried to make our workshops a simpatico experience for all, regardless of skill level. There are no entrance requirements—all you need is a digital camera capable of manual operation and a desire to make pictures in one of the most beautiful areas of the country.

Watch the SummerKeys website www.SummerKeys.com for registration information, further details and pricing. Or contact us directly at GVR@GVRphoto.com

We look forward to hearing from you and to seeing you in Lubec!

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. His photography books include Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart, and Talking Photography, a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over ten years. His latest book (done in collaboration with his wife and partner Judith Goodman) is Serenissima: Venice in Winter www.veniceinwinter.com

Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 10/10]

|