Go Back to current column

Lubec Photo Workshops – Summer, 2011 (see below)

The Sky is NOT the Limit...

...when you can tame it in-camera

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

Digital photo editing tools like Photoshop allow for effortless manipulation of photographs after the fact and seem to make up for any number of mistakes or less-than-optimal conditions that occur or exist when the photo is made.

Perhaps the most common example might be what you can do when you don’t get the right overall exposure. Levels, Curves--Highlight or Shadow sliders—these and other tools all can turn a lousy exposure into a passable one, a slightly-off exposure into a perfect one.

|

|

| Just a few tweaks in iPhoto turned my overexposed shot of a fishing boat in Campobello, NB, into a perfectly exposed one. |

But if that were all Photoshop could do it would barely be a one-trick pony. As all of us know—and that includes even a film-loving photographer like me—PS offers the remarkable opportunity to change not only all of an image, but parts of an image as well, for the kind of post-production tweaking that would be all but impossible to achieve in a conventional wet darkroom.

Photoshop’s amazing ability to select areas of a photo for near-surgical manipulation is what makes this digital tool so valuable. Using the lasso, paint brush and other tools enables one to correct flaws or remove (or even add) elements to an image while the rest of the photograph remains untouched. All before our eyes. And all—if we use layering—easily reversible if we do not like the result.

So what’s not to love?

Well, regardless of how comparatively easy the above manipulations in post might seem, they are post-production manipulations and therefore take additional time to do. That might not seem a big deal if you are working on only three or four images. But, as any serious, semi-pro or pro photographer will tell you, having to work post-production magic on several hundred or even several dozen images can quickly dampen one’s enthusiasm for even a tool like Photoshop, and make one think about getting it right the first time—next time.

The concept of in-camera adjustment to produce a perfect digital image or a perfect negative hardly is new. Ansel Adams was perhaps the best known disciple of getting it right the first time, arguing long and loud for “pre-visualization” via his Zone System of exposure calculation.

Adams assigned a set value, or Zone, to elements of a monochrome image, from the darkest black to the whitest white. By calibrating one’s exposure in advance to pre-visualize which parts of the photo one wanted to be brightest or darkest, one could be fairly certain of producing a negative that would give you what you wanted—and that would not take a year and a day in the darkroom to produce a wonderful print.

[I always thought one of the most ironic things about Adams was that his glorious prints earned him a reputation as a darkroom master whose images no one else ever could duplicate. That’s true up to a point; he was a superb black and white printer, at a level it takes years if not decades to achieve. But in truth, and in most cases, much of Adams’ heavy creative lifting was done before he got his hands wet: i.e.: in creating the perfect negative. As a practical matter Adams was intent on producing negatives that all but printed themselves—albeit at his level.]

But what happens when even the most perfect exposure calculation can’t produce a uniformly great image, or a perfect negative?

Adams’ contemporary, Baltimore’s legendary A. Aubrey Bodine, was famous for his depictions of life on the Chesapeake. In fact Bodine’s wonderful bxw photos of watermen and the like were part of the inspiration for my first book of photographs, Faces of the Eastern Shore (1992). [See below for ordering information.]

But Bodine, a photographer for the Baltimore Sun, also was a “pictorialist” fine art photographer who shared little of Adams’ reverence for reflecting a scene as it originally appeared. He had no qualms about manipulating his images after the fact (sound familiar?) even going so far as drawing on his negatives with a pencil, or scratching them, to achieve a desired effect. Ansel Adams’ work was in many ways a rebellion against the mannered style of the pictorialists. Still, one of Bodine’s techniques that I certainly can understand, given the limitations of both his film and his equipment, was his predilection for “improving” his skies, especially in his famous waterscapes on the Chesapeake.

Bodine was said to have made a series of images of gorgeous cloud-filled skies that he could painstakingly substitute in an image when the actual sky in his documentary shot was insipid or washed out.

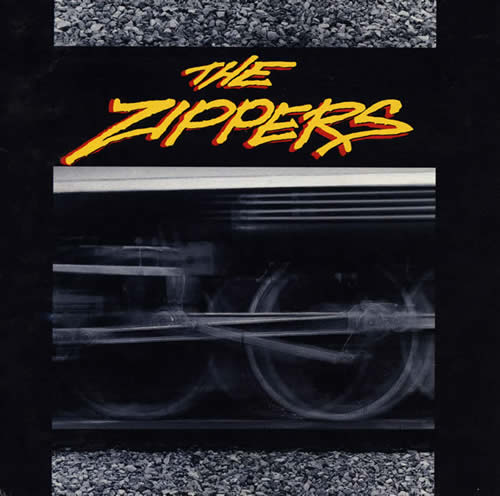

It was a bear to do—I know: I have done similar tricks in my own darkroom: once for an album cover in the days before digital. For example, instead of laboriously aligning parts of two separate negatives to create the image of a moving steam engine racing along a stationary roadbed, as I did in 1989 for the debut album by The Zippers for MCA records, I could have gotten the same effect today with a lasso, selective cutting and pasting, and an electronic airbush to soften the edges.

|

| Back in 1989 I had to make two shots--one of an apparently 'moving' locomotive (actually done with drag-flash and a moving camera), the other of the stationary roadbed--and painstakingly put them together into one silver print in the darkroom. Today, I could stitch the images far more easily on the computer. (c) Goodman/Van Riper |

All of which goes to show that there really isn’t anything new under the photographic sun.

Recently, during our just-completed week-long photography workshop in Umbria, Italy (more details on this great adventure in my next column) I was able to illustrate one way to literally “create” a dramatic sky where none was visible, and later, to balance a key foreground element with enough light so that I could register an existing sky without blowing it out.

All in-camera and both without resorting to post-production tricks in Photoshop, Lightroom, iPhoto, Bridge, etc.

When Judy and I first arrived at the Umbrian town of Cannara—the location of the gorgeous 17th century restored farm villa that was our headquarters—I noticed a brick building sitting at the edge of a freshly tilled field a few hundred yards down the road from the villa. The building was nondescript except for a beautiful rounded element at one end, decorated with ornate stone and tile work at the top.

I had to photograph it.

So one morning shortly after dawn, New York photographer Devra Goldberg and I walked down the road to the building and began shooting. We both worked in bxw, Dev with her favorite tools: toy cameras and bxw film; I with a Holga and my digital Nikon D300.

My first digital record shots, in color and bxw, showed how blah the sky looked.

A subsequent shot to bring up the sky by lessening the exposure did improve things, but the building was woefully underexposed. Rather than say, “I’ll just lighten the building later in Photoshop,” I figured out a way to immediately both darken the sky and render dramatic detail in the building—and thereby save myself sitting in front of a computer after the fact, trying to make the picture work.

|

|

|

| Early tests on the farm building were not promising. Shot only by available light, you got either the building or the sky; not both. |

The technique involved using intense flash to render the building while at the same time letting in as little available light as possible in order to darken the existing sky. This was the polar opposite of what I often do at events or weddings when we have to work in darkened banquet halls or places of worship. Then, I will use my flash normally to render my subject correctly while also slowing down my shutter speed to seemingly impossible speeds like an eighth or even a quarter of a second. This accomplishes two things: the slow shutter of the camera brings up background details beautifully while the speedy duration of the flash freezes my subject into looking tack sharp.

In the case of the Umbrian farm building, I needed the flash to really be powerful since I was planning to stop down my lens considerably to render the sky darker. Thus I could not rely on my in-camera flash’s TTL setting—that just would insure a succession of insipid flash pictures with a well-lit building and a bland morning sky.

No, here I went into full-manual mode and set my flash to full power. This gave me the freedom to set my shutter at its highest sync speed (1/250th) and, more importantly, to let me stop down my lens far more than normal to let in the least amount of ambient light and thereby darken the sky significantly to produce a really dramatic picture, even under these less-than-ideal conditions.

|

| The money shot--combining bright flash on the building with very underexposed sky to conjure up Wuthering Heights. Amazing that the first color shot and this one were made within maybe two minutes of one another. (c) Frank Van Riper |

A few days later, under less difficult conditions, I used the same technique to improve an available light photo in a vineyard.

In this case, it was a “portrait” of the legendary Sagrantino grapes that produce so many of Umbria’s delicious (and, in the States anyway, largely unheralded) premium wines.

|

|

| In this case, both shots really are fine, but if an editor needed a pic with more grape detail, it's nice to be able to provide it. (c) Frank Van Riper |

The difference was subtle, but still worth doing—especially if the photo were to be published and therefore required more foreground detail for better reproduction. An available light shot, calculated to render the clouds in the sky, left the foreground grapes a little too mark for my taste. Again using my in-camera flash, I was able to lighten the grapes and still stop down sufficiently to render a pleasingly darker sky and clouds.

Faces of the Eastern Shore

Order Frank Van Riper’s classic look at life on the Chesapeake, Faces of the Eastern Shore, for only $15 (reg. $19.95), plus s/h.

Published in 1992 and printed in duotone, this 10”x 9” quality paperback was featured in the Baltimore Sun, Washington Post and numerous other publications for its superb location portraiture and lyrical text.

Said author James A. Michener in his foreword: “What this rascal has done is belatedly to illustrate my novel, Chesapeake, and superbly.”

Contact Frank directly for copies of this now out-of-print classic: GVR@GVRphoto.com

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys – Summer, 2011

Next summer, Judy and I will once again be teaching three hands-on photography workshops in Lubec Maine, sponsored by the SummerKeys Music school. (www.summerkeys.com)

Our dates for summer 2011will be as follows:

July 11th through 15th

July 25th through 29th

August 8th through 12th

Classes are limited to only six participants each week. Each class includes personal instruction, ongoing portfolio review and a wide range of location photography, including portraiture, landscape and night shooting. Each week’s class ends with a slide show of students’ best work that is open to the public.

Since their inception in 2009, Judy and I have tried to make our workshops a simpatico experience for all, regardless of skill level. There are no entrance requirements—all you need is a digital camera capable of manual operation and a desire to make pictures in one of the most beautiful areas of the country.

Watch the SummerKeys website www.SummerKeys.com for registration information, further details and pricing. Or contact us directly at GVR@GVRphoto.com

We look forward to hearing from you and to seeing you in Lubec!

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. His photography books include Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart, and Talking Photography, a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over ten years. His latest book (done in collaboration with his wife and partner Judith Goodman) is Serenissima: Venice in Winter www.veniceinwinter.com

Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 11/10]

|