Go Back to current column

SUMMER Photo Workshops, Lubec, Maine

NEW--Join us in Umbria, Italy, in October!!

(see below)

Unavailable Light

There IS a place for Digital...really

By Frank Van Riper

Photography Columnist

If ever there was a time when I had to eat my words about my preference for film photography over digital, it was a few weeks ago when my wife and partner Judy and I were hired to cover the 2010 edition of QuestFest, the international celebration of visual theater, headquartered at Gallaudet University in Washington.

For two solid weeks Judy and I photographed rehearsals, performances and workshops done by some of the best visual artists, mimes, dancers and clowns in the world. Our portfolio included acts from Iran, Romania, Hong Kong, Canada and literally all over the United States.

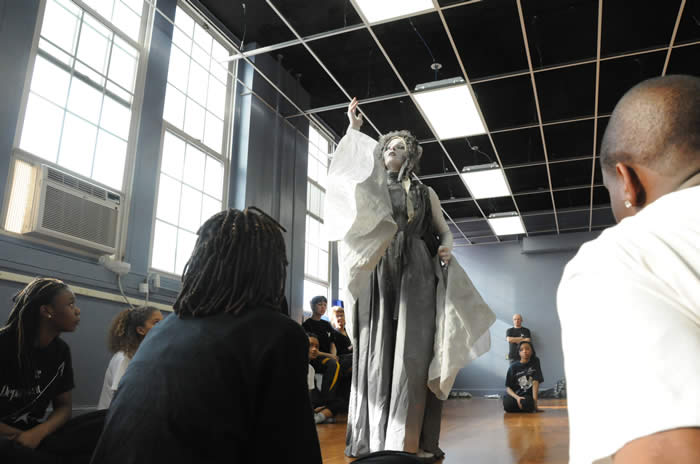

It was a visual and photographic feast during this year's QuestFest

celebration of visual theater at Gallaudet. Above, Arts with the Disabled Association of Hong Kong puts on a spectacular version of 'Journey to the West.' (c) Frank Van Riper

We photographed in large theaters, black box rehearsal halls, classrooms, cafeterias and dressing rooms; on location at a theater in Baltimore, as well as during a theater workshop at the Ellington School of the Arts in Washington. We shot with two digital Nikons: the D300 and the D90, and on one occasion the great Leica M9 that I had all-too-briefly for review. Although every so often Judy and I would use flash—Judy’s was a Quantum Q-Flash on a Stroboframe bracket; mine was a simple Vivitar 285 that I would use on or off-camera—what was remarkable about this assignment, that produced some four thousand (edited) images, was how infrequently we used our flashes and how frequently we shot only by available light—even when there was comparatively little of it actually available.

Sharpness like this would have been unheard of in the past

if shooting by available light with slow films. But with my wife's

great little Nikon D90 cranked up high, no problem.

(c) Judith Goodman

And this was no fluke. A week after our QuestFest gig, we were hired by the drama department at the Ellington School to photograph final dress rehearsal of a student–produced play, “Aftermath II—the Silence Soldiers: Breaking the Appearance of Delicacy.” It was a remarkably mature drama on gender inequity through the centuries—from biblical times to the present—and once again Judy and I opted to work by largely available light.

It was another home run—one of our shots even ran with a review on the Washington Post website.

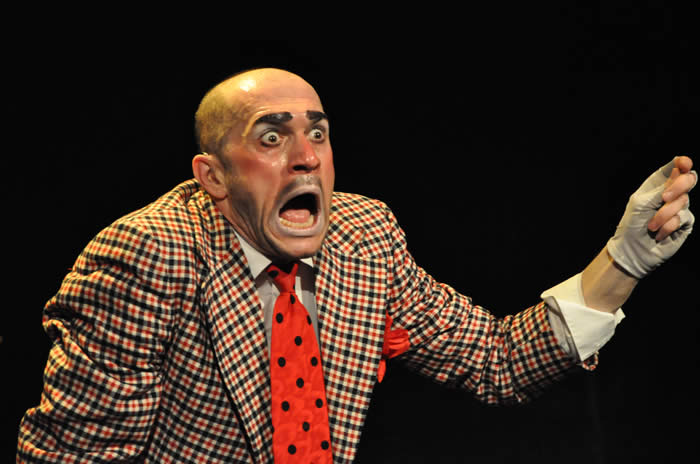

At Ellington, the Romanian troup Masca, led by director Mihai Malaimare (above) gave a rapt audience of theater majors a vigorous workshop in mime and other aspects of visual theater.

Both: (c) Frank Van Riper

It’s not that making digital images by available light is any surprise—after all, digital long has been known for its light-gathering power, and shares a characteristic of chromogenic bxw films like Ilford XP-2 of letting photographers adjust their shooting speed (ISO) at will, from frame to frame if desired. What was remarkable was the quality of the digital images produced at even the highest ISOs--3200 and beyond. [It must be noted that pushing the bejabbers out of XP-2 to, say, 3200 or 6400 will inevitably result in grainy images—desired or not.]

No—in a testament to the improvements being made seemingly overnight in the sensors of higher-end digital cameras, the photographs that Judy and I made at high ISO settings not only were good, they were remarkably grain free and certainly good enough for publication.

Two perfect examples of digital's great light gathering power. Top,

Russian-born (now Canadian) mime Max Fomitchev--"Max-i-Mime"--is caught mid-expression during a performance in an otherwise dark Black Box theater. Below, in the play 'The Intruder,' dim, atmospheric light enfolds two members of the Romanian company Masca. Remember: all these shots were made on the fly, during actual performances. Top: (c) Judith Goodman; bottom (c) Frank Van Riper

I thought back to the last time we had photographed at Gallaudet, more than a decade ago, when our friend Tim McCarty, now founding director of QuestFest, was head of the drama program at Gallaudet’s high school, the Model Secondary School for the Deaf.

During the many years that we shot MSSD shows for Tim—from “The Wiz,” to “Grease,” to “A Midsummer Night’s Dream”—the drill was infinitely more involved than the available light shooting we did for QuestFest.

First, Judy and I would watch a run-through of a show, often in final dress, during which we would make up a shot list. Then Judy and I would discuss the shot list with Tim and he would decide the sequence of the set-up shots, depending on the most convenient costume changes.

With that decided, our work would begin. We would trudge up on stage and set up a couple of large studio strobe lights with no diffusion at all—no softboxes or umbrellas--just a whole lot of direct firepower.

Why?

Because back then we most often shot in medium format on unforgiving color transparency film no faster than 200 or 400 ISO. At those comparatively slow film speeds there was no way we could make sharp images indoors, even under what appeared to be bright stage lighting, and no way that we could juice up the light onstage sufficient for our purposes without it being direct.

The formula worked, but not without its own limitations. Juicing up the light with strobes meant that we could, in theory, shoot the players at higher shutter speeds—but that would create virtually black backgrounds.

In order to register the stage lighting—which, after all, is a key atmospheric part of any stage show--we had to set up on a tripod and create that delicate mix of slower shutter speeds with flash that would freeze the subjects being lit by direct strobe light while allowing the background area that was not being hit by the strobes to “come up,” or register on the film, during the remainder of a long exposure of perhaps a quarter-second. (Trust me: in work like this, that’s a lifetime. And in these cases, even though the direct flash would help freeze the subjects during long exposures, there always was the danger of a telltale shadow around the edge of a person caused by ever-so-subtle movement.)

At the dramatic end of 'The Intruder,' melancholy blue light is a key

element of this image. Digital's light-gathering power allowed Judy to

shoot fast enough to freeze action, while the sensor recorded all the

subtlety of the lighting. (c) Judith Goodman

It was like making two separate exposures on one piece of film—not all that complicated once you master the technique, but very time-consuming. And we always had to have someone tell the players in sign language: “Stay very, very still.”

In fact, the admonition “Stay very, very still” echoes throughout a quirky new book from the National Gallery of Art entitled In the Darkroom—An Illustrated Guide to Photographic Processes Before the Digital Age (Thames & Hudson, 96 pps, $19.95)

Leafing through this elegant little paperback, I was struck by two things: first, how even in the past decade the work that Judy and I do commercially has changed dramatically, but, second, not nearly so dramatically as all that came before—when photography was in its very infancy.

The great thing about this book, written by Sarah Kennel with Diane Waggoner and Alice Carver-Kubik, is that it is small. Which is to say: rather than serve up a thick , hard-to-digest tome full of photo arcana, the authors have provided an easy to consume tasting menu briefly describing most of photographic printing’s early incarnations, from Albumin prints to Woodburytypes—many with beautifully reproduced examples.

With more and more young photographers learning digital technology (and with gratifyingly large numbers also wanting to learn the ancient secrets of analog) a book like this would be welcome as required--though hardly onerous--reading.

As Judy and I worked at Gallaudet this time around, it was easy to think back to our photographic ancestors and all the gear they had to lug with them to make photographs of subjects that didn’t even move. Yet here we were, with nary a tripod nor a studio strobe between us, making great pictures on the fly. This time, the “ambient” stage lighting was nearly always plenty for us to shoot by—and it also let us reflect the artistic vision of the lighting director, often with very dramatic effect.

This turbulent shot, made at the finale of 'Journey to the West,' would have been much more difficult to get on film. I deliberately wanted a slow speed to show motion, but needed it fast enough to render the subject--and the projected background lettering--sharply. (c) Frank Van Riper

I’ll always be a film photographer, especially for my personal work in black and white—and I always will print it myself in my own wet darkroom.

But, given the results we now are getting, it’s no surprise that our commercial work will now be all digital all the time.

The Umbria Photo Workshop

The trip of a lifetime, Oct. 16-23, 2010

Frank Van Riper Join internationally acclaimed husband and wife photographers Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman for a weeklong photographic workshop under glorious fall skies in one of Italy’s most beautiful regions.

Frank and Judy, authors of the award-winning book Serenissima: Venice in Winter, will share their image-making techniques with a small group during a week covering everything from landscape photography in the verdant hills of Umbria to location portraiture in its closely held truffle fields.

Participants will travel by guided excursion to several of Umbria’s storied hill towns, including Perugia and Assisi, and receive individual attention during daily critiques.

Package includes 6 nights in the fully restored 17th century villa Fattoria Del Gelso in Cannara, located on a 40-hectare working farm literally walking distance from colorful shops and restaurants and centrally located in the shadow of Assisi

This is a trip designed for relaxed learning and sightseeing via foot, bicycle and van, taught by two experienced location photographers whose work has been exhibited in and acquired by major museums in the United States. Frank and Judy are molto simpatico teachers who will turn your photographic vacation into a once-in-a-lifetime adventure.

October 16-23, 2010

Price per person: €1500 (convert to dollars)

Limited to 6 participants

Package includes:

--6 nights in the private villa Fattoria del Gelso

--welcome and farewell dinner

--all breakfasts

--vineyard tour and private lunch

--daily happy hour

--individual critique and instruction

--private guided walking tours

--pizza-making party at the villa

--ground transportation throughout your stay

—FURTHER INFORMATION: www.experienceumbria.com

Lubec Photo Workshops at SummerKeys

Spend a week of hands-on learning and location photography with award-winning husband and wife photographer-authors Frank Van Riper and Judith Goodman. Working from their stunning home in west Lubec overlooking Morrison Cove, (see photo above) Frank and Judy will cover basics of portraiture, landscape and documentary photography during morning instruction, followed by assignments in multiple locations including Quoddy Head State Park, Campobello Island, NB and the colorful town of Lubec itself. Daily critiques and one-on-one instruction. NO entrance requirement. Minimum age for attendance is 16. Maximum number of students each week is six . Students supply their own digital camera.

Read more about the Workshops in Frank’s column:

http://talkingphotography.com/archive/2009/photowork.htm

Frank Van Riper is a Washington-based photographer, journalist, author and lecturer. He served for 20 years in the New York Daily News Washington Bureau as White House correspondent, national political correspondent and Washington bureau news editor, and was a 1979 Nieman Fellow at Harvard. His photography books include Faces of the Eastern Shore and Down East Maine/ A World Apart, and Talking Photography, a collection of his Washington Post and other photography writing over ten years. His latest book (done in collaboration with his wife and partner Judith Goodman) is Serenissima: Venice in Winter www.veniceinwinter.com

Van Riper’s photography is in the permanent collections of the National Portrait Gallery and the National Museum of American Art in Washington, and the Portland Museum of Art, Portland, Maine. He can be reached through his website www.GVRphoto.com

[Copyright Frank Van Riper. All Rights Reserved. Published 4/10]

|